The following article appeared in the Wellesley Townsman on October 29, 2015.

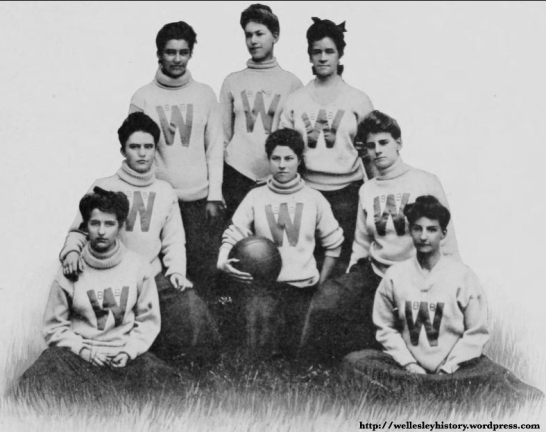

1902-03 Wellesley College Varsity Basketball Team

Source: 1904 Legenda

Baseball may be America’s pastime. But the most popular team sport in this country is, in fact, basketball. According to the 2009 Federal Census, over 24 million men, women, boys, and girls shoot hoops.

This number, however, would not be nearly that high if one Wellesley College instructor had gotten her way over a century ago. Her name was Lucille Eaton Hill and she was the Director of Physical Training at the college. To her, basketball was a “great evil” that was detrimental to both a female’s physical development as well as her feminine nature. Simply put, basketball was unlady like.

What might sound like utter nonsense today wasn’t received that way back then. Rather, her words sparked a national debate about whether girls and women should participate in the sport.

The year was 1903 and basketball was in its infancy. Only 12 years earlier, James Naismith invented the sport at a Springfield YMCA in order to develop an indoor exercise for men. Almost from the beginning, this new activity caught on at women’s schools and YWCAs — albeit with a different set of rules. While the men’s rules fostered aggression and competition, the women’s game was more reserved and necessitated cooperation and teamwork.

Such a dichotomy between men’s and women’s basketball is not surprising given the gender roles that existed at the time. Men were the wage earners, with women by and large relegated to the home, their chief responsibility birthing and raising children. Therefore, society in general dictated that any female activities should not sacrifice the health and social respectability of women.

Yet women’s basketball was initially viewed quite favorably in the 1890s. One of the leading promoters of the sport — Smith College’s Senda Berenson — remarked that basketball “combined the physical development of gymnastics and the abandon and delight of true play.” It’s no wonder that this new activity quickly became all the rage within schools, athletic centers, and civic groups.

This most definitely included Wellesley College. Up until that time, exercise was confined primarily to the modest gymnasium on the second floor of College Hall. The only outdoor sports were tennis and crew — which were then far more recreational than their modern form. Basketball provided that energetic release that young women were craving.

Anti-basketball crusader Miss Lucille Hill was actually quite a proponent of the sport at first. As the Director of Physical Training, “Gym” Hill — as she was known around campus — had a playing field constructed in 1893 between what is now the Schneider Center and Lake Waban so that her students could play basketball. (Back then this sport was often played on grass, as dribbling was limited within the women’s game. Players would simply pass the ball around until one of them had an open shot.)

Hill’s war on basketball began about a decade later after years of observations of the effect this sport had on young women. In particular, she felt that basketball — with its potential to cause overexertion and too much competitive enthusiasm — jeopardized their physical, mental, and moral health. Such a belief jived with another one of her philosophies that learning to play a sport should be no different than learning an academic subject. It must be taught by professionals who understood the game and cared more about correct technique than winning or losing.

The first attack came during a speech by Hill at a meeting of the New England Association of Colleges and Preparatory Schools in October 1903. After describing the general state of what was wrong with how girls and young women approached athletics, she directly targeted basketball. Her recommendation was blunt: “Basketball should be stopped for young girls, until it is controlled on a physical basis; and interscholastic matches should be absolutely stopped on the basis of undue excitement and the tendency to develop a most undesirable, unwomanly feeling in regard to publicity, the exhibition of physical prowess before a mixed audience. There must be a social stigma against competitive games for young girls, so that no mother will permit her daughter to do such an illbred thing.”

The press ate up her words. Headlines in the New York Times and Detroit Free Press blared “Basket Ball Denounced” and “Basketball A Menace: Wellesley Director Argues Against Game.” Academic journals furthered the discussion with comments and opinions from athletic and medical professionals.

And for a brief time, it really did look like the future of basketball for young women was at risk. But for reasons unknown, by the end of the following year, the movement had more or less died. Basketball was never even banned at Wellesley College. Perhaps the game was just too darn popular.

Of course, this isn’t to say that questions regarding the effect of basketball on female health and wellbeing went away anytime soon. In fact, it wasn’t really until the women’s liberation movement during the second half of the 20th Century, and the enactment of Title IX in 1972, that people accepted that basketball — even the men’s more aggressive style of play — was not harmful to the development of girls and young women.

As for Lucille Hill, her legacy doesn’t appear to have been sullied by her failure to squash basketball. But then again, her tenure at Wellesley College lasted only several more years, until 1909, when she entered into a kind of social service, leading various programs that taught health and athletics within rural communities, mill towns, and urban areas in the Northeast.

Hill died in Boston in 1941. The College community briefly acknowledged and celebrated her professional career — she was, after all, a pioneer in the field of female athletics and physical education. Interestingly, however, all of these tributes failed to mention one important footnote to her life: that for a brief moment, Lucille Hill was at the center of a significant, but often neglected chapter within the rich history of America’s most popular sport.