The following article appeared in the Wellesley Townsman on August 6, 2015.

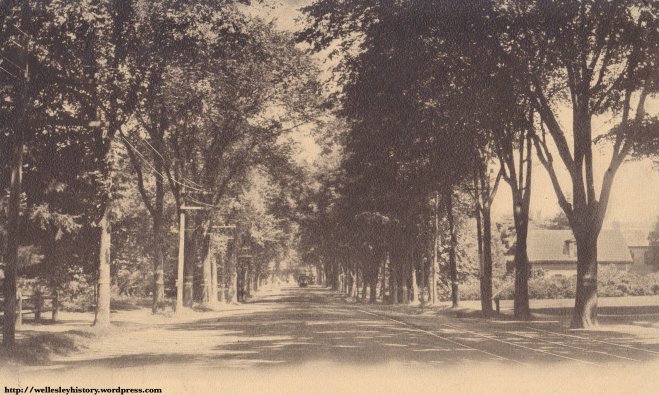

Washington Street in Wellesley Hills during the early 1900s

Fun fact: The Town of Wellesley has been recognized by the Arbor Day Foundation as a “Tree City USA” community for a Massachusetts-record 32 consecutive years. An honor of a municipality’s commitment to a tree management program, this designation is proof that Wellesley is among the leaders in the preservation and enhancement of open spaces and community forests.

This isn’t to say, however, that Wellesley wasn’t worthy of accolades prior to its first acceptance of this award in 1984. In fact, for well over a century, Wellesley has had a reputation as a town that cared deeply about its trees and parkland.

Of particular note were its street trees. Beginning in the 1850s and 1860s — as Wellesley first recognized the importance of village beautification — its citizens planted hundreds of shade trees along the sides of its major roads. Their motive was simple. Build a beautiful town, and you’ll attract new residents who shared those same values.

American elm trees were especially good for this purpose. There are few scenes as picturesque as a road lined with stately elms, their canopies reaching far across the street, creating the illusion of a suburban forest.

By the 1870s, this effect had taken full force in Wellesley — most notably along the stretch of Washington Street in Wellesley Hills from Walnut Street to Forest Street. So much so that the tavern that anchored Wellesley Hills Square since the early 1800s changed its name to the Elm Park Hotel.

Sadly, however, if you drive along Washington Street today, you’ll see a vastly different picture. Few, if any, elms can be found along the street.

But please note this has absolutely nothing to do with Wellesley’s commitment to its trees. Rather, it’s almost entirely the result of two separate factors: the modernization of roadways and disease.

Quite simply, many elms had to be removed as roads were widened. Remember, way back when these trees were planted, streets were nothing more than enlarged dirt paths. They were often narrow, rarely perfectly straight, and not conducive for modern travel. It was therefore understandable that once streetcars and automobiles arrived in Wellesley at the turn of the 20th Century, many of these trees had to be cut down for safety reasons. You just couldn’t have so much traffic — not only cars and trolleys, but also horses and pedestrians — within such narrow confines on such antiquated roads.

Those elm trees lucky enough to survive, however, were met with an arguably more destructive force: Dutch elm disease. It’s the reason there are so few native elms, not just within this region, but in all of North America. Literally tens of millions of elm trees on this continent have succumbed to this disease since it was introduced from Europe in 1928.

Primarily spread by the elm bark beetle, Dutch elm disease is a fungus whose spores are deposited within the inner wood of elm trees as these insects eat away at the tree bark. The fungus then grows and expands, setting off a defense mechanism whereby the tree clogs its own vascular tissues in order to stop the spread of the fungus, but thereby prevents the transmission of nutrients and water. Once infected with the disease, elm trees quickly wilt and die, often no more than a year or two later.

What makes Dutch elm disease so ravaging is that there is no known cure and can spread easily as infected beetles fly from tree to tree. In addition, it can be transmitted through the grafting of tree roots. It’s therefore critical to remove an infected elm as soon as possible following detection of the disease.

Wellesley officials first became concerned about Dutch elm disease around 1934. Having already experienced a blight of the American chestnut trees that wiped out the entire population in the early 1900s, tree experts were acutely aware that a sustained commitment by the town was necessary to stave off Dutch elm disease. Everyone had to be on the lookout for sickly elms and take immediate action once the disease was found, lest the thousands of elm trees in Wellesley disappear.

It was largely a waiting game during the 1930s and 1940s. As reports of positive tests for the disease came in from communities across the nation — including within neighboring cities and towns — Wellesley took whatever proactive measures it could to limit the chances that Dutch elm disease would show up here, including eliminating the piling of dead elm wood that could act as breeding grounds for the disease, as well as continually spraying trees with insecticides to control the elm bark beetle population.

The first confirmation of Dutch elm disease in Wellesley occurred in 1948 within an elm tree on Great Plain Avenue near the Needham line. It was at this point that the Town adopted an even more aggressive approach to try to prevent an outbreak. Whenever any tree showed signs of infection — whether on public land or private property — Town officials would remove it at once at the Town’s expense. (In 1939, a state law was passed that allowed municipal workers to remove diseased trees without the owner’s consent.)

Wellesley was arguably more successful in combating this disease than most communities. Nevertheless, it still took its toll on the town’s elm trees. By 1951, there were 88 cases of Dutch elm disease in Wellesley. Two years later, that number had doubled. And for the next two decades, an average of 200 infected elm trees were removed each year.

This unfortunate reality was perhaps one of the primary reasons that in 1974 the Town chose to stop funding the removal of infected elms on private property. Although officials would still help identify sickly trees, the costs of cutting down the trees would be passed on to the homeowners.

The fight against Dutch elm disease was just too difficult. In particular, the banning of DDT – one of the most effective insecticides on the market — gave little hope that the elm trees would not eventually become infected. So one by one, many of the remaining American elms that Wellesley’s forefathers planted a century earlier disappeared.

But let’s not miss the forest from the trees here. In recent decades, although the number of large street trees has been decreasing for reasons out of our control, Wellesley has been ambitiously planting shade trees throughout the town. Perhaps not literally next to or on the roadways, but many close nearby. This even includes elms, albeit species that are more resistant to Dutch elm disease.

No one should therefore question Wellesley’s investment in its tree population. With over 150 years of sustained commitment toward the protection of our community’s trees, we have put ourselves in a great position to maintain that level of excellence for many years to come.