Message from Josh: This blog turned one year old last week. I’d just like to give a heartfelt thanks to all of you for reading my posts and sharing them with your friends and family. Please continue to spread the word. The only way we’re going to help improve the state of preservation in Wellesley is through increased awareness of the town’s historical treasures.

Fun fact: At its peak, there were twelve elementary schools in Wellesley — five more than there are today.

Some of you probably already knew that. But did you know that the site of only one of those elementary schools — Warren — had been the location of a school for nearly 200 years? Think about that for a second. Up until Warren closed in 1987, children had passed through the doors of that schoolhouse — or one of its five predecessors — each year since the second term of the administration of George Washington!

So where was the school in that end of town located before the first schoolhouse was constructed on this site? How about nowhere! This was, after all, prior to the establishment of school districts within the Town of Needham. The only “schools” were nothing more than houses where paid citizens taught children how to read and write. The importance of the site of Warren School — that triangular parcel of land at the intersection of Washington and Walnut Streets — therefore cannot be overstated. It literally marks the birthplace of the Wellesley Public Schools. The fact that these specific school grounds were also the site where our public educational system developed over the next two centuries makes it that much more special.

(To be precise, there is record of the sporadic use during the 1700s of very primitive schoolhouses on Church Street and at the eastern end of Linden Street, as well as one that was carted around town to the different population clusters. Click here to read more about the early history of public education in Wellesley.)

The first schoolhouse on the site of Warren School wasn’t built until around 1796, eleven years after Needham officials voted to divide the town into school districts. Of course, this school wasn’t known as Warren — which was only used for the 1935 schoolhouse. Instead, it was referred to either as the North District Schoolhouse (or simply, North). In fact, the first five schoolhouses all used that moniker.

But why North instead of East? Wasn’t the school located at the eastern edge of Wellesley? Remember, however, that Wellesley was still a part of Needham at the time. And if you look at a map of what was then Needham, the region the school served — encompassing all of what is now Wellesley Hills, Wellesley Farms, and Lower Falls — was the geographical northern section of the town.

Let me now clear up your mental image of this schoolhouse…because it was nothing like what you or I consider to be an adequate facility for the education of our youth. Based on the few descriptions of the structure that exist, it was pretty much a large unpainted shack with a window here and there to let in some light. And inside, there was little more than several benches and the ever-important box stove that kept the children warm (enough) during the winter.

This is totally understandable, however, because we’re talking about public education in a poor farming town at the turn of the 19th Century! “School” still consisted of nothing more than getting all of the young children into a single room and teaching them the basics of reading, writing, and grammar. Once they learned that, it was back into the fields.

But it’s also undeniable that North got the short end of the funding stick compared to the other district schools. That’s because, unlike today — when the budgets of each of our elementary schools are comparable, resulting in parity between the schools — up until the late 1800s, the budgets of the district schools were determined entirely by the Town Assessor. The more taxes collected in the district, the larger the budget of the district school. In other words, if you resided in a poorer or underdeveloped part of town, you were stuck with an inferior school.

This was especially true for the North district. In 1805, for example, its annual budget was $94.79 compared to $122.90 for the West district — the other school district in what is now Wellesley. The wealthiest district, for what it’s worth, was the Great Plain district at $155.36. (Yes, there was a time when Needham was richer than Wellesley…)

Over the next three decades, however, the North district grew rapidly in terms of both population and wealth, due mostly to the growth of the paper manufacturing industry in Lower Falls. By 1836, North had the largest annual budget of all the district schools in Needham.

This increase in population and wealth — along with a vote from the Town to “equalize” all of the different district schoolhouses — led to a new North District School building in 1833. Unfortunately, just as with its predecessor, we don’t have that many details about this second schoolhouse. Nor do we have much information about the third or fourth North Schools, built in 1842 and 1858, respectively. It’s fair to say, however, that each school was larger and more modern than the preceding one. And how do we know this? Well, it helps that the second and fourth buildings still exist.

Second North District Schoolhouse (Built 1833) — Now 31-33 Columbia Street

Sold in 1842 to General Charles Rice, who moved it to the rear of his estate on

Washington Street in Lower Falls and converted the structure into a two-family dwelling.

Fourth North District Schoolhouse (Built 1858) — Now 56 Washington Street

Sold in 1874 to William C. Heckle, who moved it to the corner of Washington

and Crescent Streets and converted the structure into a single-family residence.

(The first and third schools were also sold and moved at the time of the construction of their successors. The c.1796 schoolhouse was relocated across the street near the current site of 135 Washington Street, but later was razed or burned down. The 1842 schoolhouse was sold to someone named Jennings, but where it was moved to is unknown.)

We also don’t know much about what went on inside of these schoolhouses. To my knowledge, there just aren’t any documents that record the day-to-day activities of the schoolchildren. So we’re left wondering what it was like attending school in Wellesley up through the mid-1800s.

The best we can do is piece together some facts here and there, most of them coming from the Needham Town Reports. Consider, for example, a breakdown of the North District School budget for the year 1851:

- Sarah B. Kingsbury: teaching 16 weeks ($80)

- William Pierce: wood ($21.51)

- Ebenezer Smith: sawing and splitting wood ($6.62)

- William L. Clark: cleaning house, pail, broom, etc. ($7.60)

- Z.R. Tappan: teaching 18 weeks ($72)

- G.E. Clark: teaching 17 ½ weeks ($175) and building fires ($5)

This is pretty typical of each annual budget. The vast majority of the money went to pay the teachers while the rest went to cleaning the schoolhouse and procuring/preparing firewood (or coal after the construction of the 1858 schoolhouse). But what about teaching supplies? Ha ha. Very funny. This was loooong before projects and activities became commonplace in the classroom. Classes pretty much consisted of only repetitive exercises and recitations. All a student needed was some ink or chalk — which was either supplied by the teachers or donated by local citizens.

It also helped if the children had schoolbooks. Obtaining these, however, posed many problems because, unlike today, it was the responsibility of the parents to purchase schoolbooks for their sons and daughters. Unfortunately, few parents cared enough about the education of their children to buy the recommended books. The result was that many students had to share books or teachers needed to create individual lessons for each and every student based on what books were available. The teachers therefore were very thankful when, every so often, local citizens would donate a set of schoolbooks to the class.

It’s also difficult to determine the school calendar with any precision. But we do know that there were two 16 to 18 week terms in the summer and winter — presumably, children had to help out on the farm or in the house during the spring and fall. Not surprisingly though, attendance during the winter was almost entirely dependent on the weather. If you lived a few miles away from school or far off the main roads — which were the only ones plowed — it really wasn’t very safe to try to walk to school. In fact, a significant number of students weren’t even enrolled in school at all because the school was too far away. This was one of the main reasons that, in 1854, a new district school was established in Grantville (Wellesley Hills).

(One can’t stress enough the importance of the creation of an additional school district. It wasn’t as if parents could homeschool their children before shipping them off to junior high. If you didn’t attend the district school, you didn’t receive any schooling. The only other level of education available in town during the 19th Century — high school — wasn’t established until 1865. But that was reserved for only the brightest of the older students at each district school.)

A huge turning point in the history of North School came in 1874 with the construction of the fifth schoolhouse. Although the town was still far from becoming a modern and affluent suburb, its officials realized that the only way to develop was to invest heavily in its schools and their facilities.

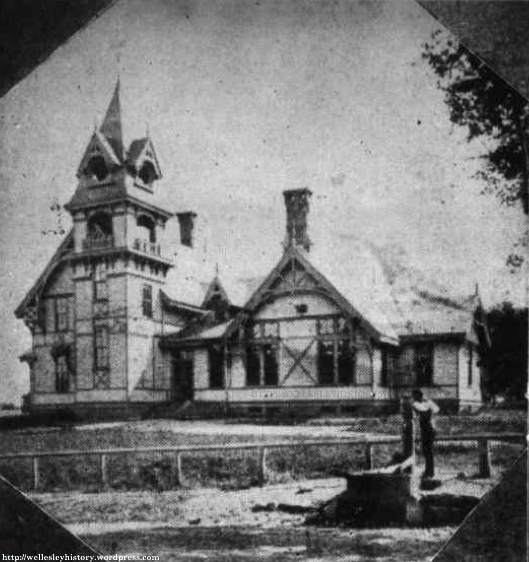

Designed by Peabody & Stearns, one of the most notable architectural firms in the Northeastern United States during the late 19th and early 20th Centuries — its architects also designed the Custom House Tower in Boston and many of the mansions in Newport, Rhode Island — the 1874 North Schoolhouse was an incredible improvement over its predecessor. It was also among the most architecturally unique buildings ever constructed in Wellesley. But that’s probably obvious from the photograph above, which was taken prior to 1897 when the right half of the school was literally raised upwards so that more classrooms could be constructed below — which is a real shame because it took away much of the character of the original building.

A few other interesting tidbits from the pre-1897 photo of the North School:

- Notice that fence separating the school grounds from the road? It’s said that the fence wasn’t put up to keep schoolchildren from running into the road — after all, the only “traffic” back then was the occasional carriage or horseback rider. But rather the fence was there to keep the cows that were used to trim the grass within the school grounds.

- Also take note of the well in the foreground (and what looks to be a person standing next to it). This makes me think that the photograph was taken much earlier than 1897, as indoor plumbing in Wellesley — at least the water supply part — dates back to 1884. Although it’s true that many open wells survived long into the 20th Century, Washington Street — the road seen in that photo — was one of the first to have underground pipes.

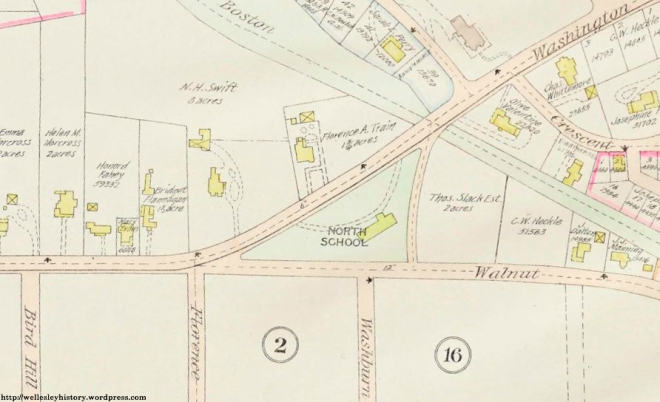

- Based on the presence of the road in the photo, you’re probably confused now about the orientation of North School. See, unlike Warren, the 1874 schoolhouse fronted on Washington Street. It was also located on the western end of the school grounds closer to the intersection of Washington and Walnut Streets — as were all four of the previous school buildings. But that’s because there really wasn’t anywhere else to put them as the school grounds only extended as far east as the edge of the hill that slopes down towards the current site of the playground.

I hope this map doesn’t further confuse you. It’s a bit disorienting because there’s a tiny (now extinct) street just to the east of the North schoolhouse. This road — which was actually the vestige of Washington Street before the main road was straightened many years earlier — used to separate the original school grounds from the current site of Warren, but was wiped off the map in 1930 when the Town was able to acquire the latter tract of land (which was used for a long time as a dumping ground for trash and other refuse). The children needed a playground and what better place to let boys and girls play than on an old dump?

The existence of this playground, however, was short-lived. By that point in time — actually as early as the late 1910s — the old North schoolhouse had become woefully inadequate. It was way too small — 40 to 50 students in a single classroom was not uncommon! — but perhaps more importantly, its wooden exterior and frame structure was a definite fire hazard.

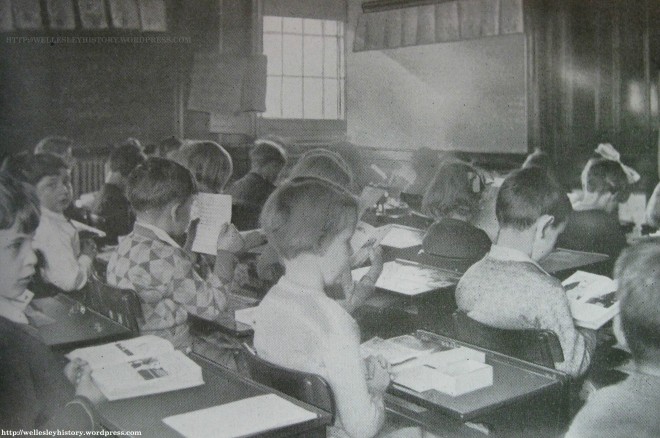

Crowded first grade classroom in Fifth North District Schoolhouse

Source: Wellesley Town Report (1930)

However, a new schoolhouse was years away. The Town was far too preoccupied constructing five new elementary schools — Hardy, Kingsbury, Sprague, Brown, and Perrin — a result of the near doubling of the town’s population during the 1920s as Wellesley evolved into a commuter’s suburb. The old wooden schools — North, Hunnewell, and Fiske — would just have to wait.

The other complicating factor in building a new North School was that once its turn came, the discussion regarding funding the project coincided with the debate over whether to renovate or rebuild the High School (then located on Kingsbury Street on the current site of the Middle School). You have to remember that this was smack in the middle of the Great Depression, and although Wellesley was relatively insulated from the economic downturn that devastated the country, there were several fervent anti-tax groups during the 1930s that did what they could to reduce Town spending.

In 1933, after upwards of four years of debate, the townspeople were finally able to agree to a plan where the Town would apply for a 30% subsidy from the Federal Emergency Relief Fund for the construction of a new North School and the renovation of the High School.

(Although the Federal Government approved the request, the bids received for the renovation of the High School came in over budget, resulting in the renewed debate over whether a new high school was a better option. It wasn’t until 1937 that construction began on a new high school at the rear of Hunnewell Field. In spite of all this, the Town managed to build a new North School two years earlier.)

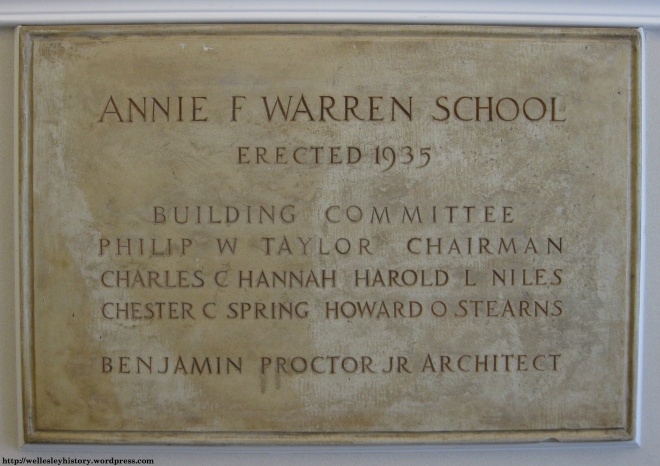

The new North School was, of course, what you and I know as the Annie F. Warren Elementary School.

Designed by Benjamin Proctor Jr. — a Wellesley resident and the architect of the Isaac Sprague Memorial Tower and the Community Playhouse, as well as numerous other buildings throughout the town — the new schoolhouse and its neo-Georgian architecture was a significant departure from that of the 1874 North School.

Although there’s little about the new school to find fault with — it certainly was an impressive building — I have to express disappointment that they didn’t carry on the North name. It had, after all, been a part of the town’s history for 139 years and connected this part of Wellesley back to the days when it was a community of farmers and mill workers in the north section of Needham.

But at least they renamed the new building after a well-deserving figure: Annie Frances Warren. A teacher (and principal) at North from 1885 to 1910 — and an instructor of English and mathematics at Phillips Junior High for ten years after that — “Nanna” Warren (1860 – 1923) helped guide North through such changes as the implementation of grading and the school’s transition from a district school (with grades 1-9) to a regular elementary school. Few educators in Wellesley history have had a more lasting impact on the town’s youth.

I also take solace in knowing that the Warren family name has now been forever immortalized. The Warrens used to be a really big deal in Lower Falls, most notably because of Annie Warren’s father, Daniel. Born in Ireland and arriving in the United States in 1852 with only one dollar and twelve cents in his pocket, Daniel Warren managed to establish a lucrative express business in Lower Falls, delivering coal, hay, and grain throughout Wellesley and the surrounding communities. He also participated heavily in Town government — something that was relatively uncommon for an Irishman — and was even the first Irish-born resident in either Needham or Wellesley to sit on a jury. In 1910, however, Warren’s Express — which had been carried on by two of his sons — was acquired by another delivery business and the Warren name began to fade into obscurity.

But Warren Elementary School kept it alive. And even today — despite the fact that the school closed in January of 1987 following the renovation and reopening of Schofield — everyone knows of the name Warren…if only because of its insanely popular playground or that the former schoolhouse is now the headquarters for the Town’s Recreation and Health Departments (after serving as studio space for local artists through the 1990s).

I’m also pleased that they’ve kept Warren looking pretty much the same (at least from the front) as it did when it first opened in 1935. Unfortunately, the interior of the school has been almost entirely modified in some way or another — most notably with the addition of a new (albeit very functional) gymnasium. The only piece of the original school that still seems to rest intact is the dedication tablet inside the main door.

But I can’t really complain all that much. There are still few places in Wellesley that are as aesthetically pleasing yet so historically significant as the Warren school grounds.

Sources:

- Needham & Wellesley Town Reports

- Map of Needham, Massachusetts by Henry Francis Walling (1856)

- Boston University Year Book (1882)

- Atlas of Wellesley, Massachusetts by George W. Stadley & Co. (1897)

- Biographical Review, Volume 25 – Containing Life Sketches of Leading Citizens of Norfolk County, Massachusetts (1898)

- Wellesley Townsman: 22 July 1910; 12 September 1919; 26 January 1923; 8 March 1929; 21 March 1930; 11 April 1930; 1 August 1930; 17 November 1933; 1 December 1933; 12 January 1934; 20 April 1934; 20 August 1934; 19 October 1934; 9 November 1934; 1 February 1935; 25 October 1935; 5 December 1935; 6 October 1937; 24 May 1956; 15 January 1987

- History of Needham, Massachusetts: 1711-1911 by George Kuhn Clarke (1912)

- History of the Town of Wellesley, Massachusetts by Joseph E. Fiske (1917)

- The Harvard Graduates’ Magazine, Volume 26 (1917)

- St. Mary’s Cemetery in Needham, Massachusetts

All uncredited photographs were taken by Joshua Dorin.

Great article again! Thank you for all the research you must do!

It looks like the tree that was planted by my first grade class in 1957 was removed. It was in the right corner of the main body where the first class area was. To the right of that was the larger body kindergarten area.

Richard Cunningham [1854-1941] kept the fires at 4th North and got $2.00 a year for it. “Think what you can buy with all that, Dick,” he was told (think that was Mr Sprague). Cunningham’s father was mortally wounded in the Lower Falls mill; his mother froze to death a year later on Florence (now Longfellow Road). He made his money the old-fashioned way for an Irish orphan: he married it. The poorest best-looking boy married the homeliest, richest girl, Hattie Louise Beck [186-1949] (remember her); the Becks lived near where the WH Library is today. She was a Proctor as well, and her cousin was Benjamin Proctor, Jr, the architect of 6th North (Warren, 1935) and, if my eyes served me, of a building at Proctor Academy. Proctor was a good architect. He also has work at Babson and, of course, the now-destroyed Gamaliel Bradford High School was in part his. The Cunninghams lived at 400 Worcester Street until he died (1941) and she (1949). Hattie Louise Beck Cunningham, a Dean graduate, was a founder of the Town (1881); he just helped, but he brought in the Irish of the Falls because they trusted him; he served as Assessor of the Town for 50 years (none, Irish, Italian, or Yankee, rich or poor, paying what he couldn’t afford). The town had only 2500 people when he died in 1941; in a generation it grew 10X — and nobody stood at the borders checking family trees, a duplicitous myth Wellesleyans have had to suffer since. Of Wellesley’s faults (and it’s had a few), discrimination on anything but affordability was not one of them. Wellesley was a hot house, a seedbed, a weedbed of diversity right from its founding. It’s even had a few 3rd mortgages and unpaid paperboys! But Wellesley’s advantage is in the way it is run; and it’s run as well as its citizens demand. Its only weakness is in nature; boys and girls don’t run on the same development schedule (or why did I go from a D student in Wellesley to valedictorian in a much-tougher, all-male private school?); that’s because (1) I was prepared well, but (2) the times are out of joint (and Wellesley with it). Can Wellesley deal with that problem? I doubt it. It takes more than Boys and Girls entrances to the classroom (which Wellesley once had), more than boys lockers and girls’. It needs (OMG) sex segregation, and that is as impossible today as one-size-fit-all failed yesterday; but if any town can solve that dilemma, Wellesley can. The brains are there; but does its will have the guts to face that problem which nature puts in our road to prosperous posterity? The road to South Natick is different than the road to Natick; and everybody in Wellesley comprehends that implication.

Great memories. Thank you for the rich detail! I attended Annie F. Warren from start to finish, so to speak — K-6. My teachers included Sylvia Whitaker Beach (grade 3), Alene Abate (grade 4) and Edna Penwarden (grade 6). Classmates included Gilbert Cass and Deborah Marchionette — forgive my spelling. We spent sixth grade in a nontraditional classroom created with massive, movable walls that I recall as being in the auditorium. We tried to make a United Nations flag from white cloth, but when we attempted to add the “logo” with blue paint, the latter seeped through onto the floor. Wilbur J. Rook was the principal. I wrote a radio play about St. Nicholas that was broadcast from his office. One winter we were able to ski to school and PE had some of us skiing down the small hill on the playground.

Edna! Good gods and goddesses! The only 1st name of a teacher I knew was Edwina Lareau, frankly, the only teacher at Warren (with Miss Whitaker) whom I remember with love and respect. 5th grade. She had a classroom in the north wing. Miss Lothrop, the school nurse, gave boys shots in the butt, pants down, in the hallway with everybody nonchalantly amusing themselves as they passed by (girls went to “the office”), preparing us, I suppose, for the indignities of our Selective Service exams at the Boston Army Base where I bumped into a like-minded Jim Fitzgerald. Another stellar walk-on part was played by a Miss (Mrs?) Burns who, on blue moons, came to the auditorium in the cellar and played 2 or 3 wobbly notes together on a pitch pipe, expecting a cheerful chorus such as we to break into Beethoven’s 9th acapella; there was a piano there, but the affectation is memorable. A note of correction for art-history majors: Jackson Pollock did not invent spatter-dribble-painting. My class did, after Mr McLaughlin cleaned up our invention of toe painting in primary colors. Well I remember Mr McLaughlin, our janitor (whose beautiful daughter was in my class), who would traipse in and clean up regurgitated urp which had been hurled over sometimes three (3) inkwells onto the bespattered students round about. Ah, the romantic aura of disinfectant, scented with pine tar, rag mop in pail, and Mr McLaughlin’s strident forbearance. Mr Pollack might have improved his technique under Mr McLaughlin, cleaning up some of those horrific messes he made whilst intoxicated; we were not! IIRR, Mrs Penwarden’s husband was a “law-enforcement official”, though I’ve oft wondered if she wouldn’t have made an equally effective one-man military police detail, wafting a billy club instead of a metal-edged ruler. Edna (1st-floor rear)! What a revelation! only proving that not all kids giggled through their teachers’ salaries in the Town Report. (Needless to say, those who did thought the faculty grossly overpaid; after all, in our day, when we fought our way through 10-foot snow drifts, teachers just turned pages in plan books and we students educated themselves). Forgive the misspellings; Edna would keep me after again! (Do you know, because Hersey and I were whispering excitedly about the last episode of Murania coming up that afternoon, that I had to wait 50 years! 50 years! to see that last episode. She has never been forgiven, and she isn’t now! Some things are simply unforgettable — though I can’t say I ever remembered (or knew) her first name. Edna! Carol Burnett in ‘The Remembrance of Edna’ in “As the Stomach Turns”. Call for Mr McLaughlin … the bucket and the mop …!

Hi bootsboneromanov! (What a handle!)

Thank you for your essay and your service to our country.

You will probably find my reply stream-of-consciousness and repetitious. I hope, however, that it evokes a few more memories!

Janitor: You may well be right about his name. I think he had red hair and was very thorough.

Edwina Lareau: She was my 5th-grade teacher, too. Lived in Cochituate. Great vocabulary builder.

Sylvia Whitaker (married name Beach): She was my third-grade teacher. The other third-grade teacher was Mrs. Gatto. I recall they traded disciplines during one class period. Mrs. Beach taught penmanship. Can’t remember what Mrs. Gatto taught.

Mrs. Penwarden: My sixth-grade teacher. I adored her. She drove a black 1951 Chevrolet sedan and lived in Alston.

Miss Pierce: Was my second-grade teacher. I recall her standing once in the doorway holding two boys, each facing the other, by the scruff of the neck and saying, “Mrs. Pierce loves children.”

Aileen Abate: My fourth-grade teacher. From the South. She showed us how to make mobiles from wire and clear plastic, which we colored and then hung from rafters or something over the auditorium stage. Someone then illuminated our fanciful creations by focusing the light from a projector on them.

Nurse Lothrop: I vaguely recall her.

Murania and Pollack and Hersey as yet ring no bells. Sorry. And thank you for this walk down memory lane. Take care …

The mention of the sale to trucking business..from Warren. Was sold to Charlie Holmes of Walnust St it became Warren Express. My dad Arthur Watsonat 23 Walnut s worked for Charlie..then Charlie sold Warren Express to my dad a Wellesley native

He changed the name to Watsons Express.

Self employed.

Pingback: 46 – The Shit-Stirrer | ghosts in the burbs

I was happy at the Warren School. At least the building hasn’t been destroyed by a contractor!