This is my first collaboration. Tycho McManus, a college junior who lives on Mulherin Lane — right near where I grew up on Standish Road — approached me about the idea of co-writing a post on Longfellow Pond, a small body of water situated within the Rosemary Brook Town Forest that both of us spent much time around during our youths. What follows is the product of this collaboration.

Living in Wellesley can be rough if you’re a nature lover. There really aren’t that many places in town where you can escape the sights and sounds of suburban life. That’s precisely why Longfellow Pond is so great. It’s one of our few natural oases in an almost entirely developed town.

The irony, of course, is that Longfellow Pond is not natural. Rather, it’s entirely man-made and, furthermore, very little of the surrounding environment has been untouched by humans. Look closely and this should be obvious, from the dam and concrete piers at the north end of the pond to the mysterious boulder marking the Hastings family burial plot. (Not to mention the sewer and gas lines that run underneath the pond.)

But that evidence of human activity doesn’t even come close to providing the complete story about Longfellow Pond. In fact, there were probably few places in Wellesley that were ever dirtier, noisier, and more heavily polluted.

Before we get to that part of the story, however, something needs to be said about the origins of the pond. Unfortunately, the details regarding its creation are a bit fuzzy. The only piece of evidence is a single sentence from Joseph E. Fiske’s History of the Town of Wellesley, Massachusetts: “On Worcester Turnpike, Rosemary Brook — now Longfellow Pond — was dammed and a mill built by Charles Pettee in 1815 for a nail factory.” But Fiske doesn’t give us any details on who Pettee was or why he chose to dam the brook.

Our best guess is that the answers to those questions have something to do with the industrial activities in Newton Upper Falls — in particular, the Newton Iron Works, which began operation in 1800 in the vicinity of Hemlock Gorge (south of Worcester Street at the Wellesley-Newton border near the current site of Echo Bridge). At that time, the process of manufacturing nails using machinery (rather than forging each nail by hand) had just been invented and was a crucial part of the first wave of the Industrial Revolution. Given the success of the Newton Iron Works on the Charles River, perhaps the industrialists that set up those factories saw nearby Rosemary Brook as an opportunity to manufacture even more nails.

So who was Charles Pettee? In short, we haven’t got a clue. Although there is record of a “Charles F. Pettee” who owned land in the vicinity of Hemlock Gorge and was a part of village life in Newton Upper Falls during the 1820s and 1830s, there is nothing to link him directly to Longfellow Pond. It also could be that Charles Pettee was related to Otis Pettee, the longtime superintendent of the Pettee iron and cotton mills along Hemlock Gorge beginning in the early 1820s. But neither Charles F. Pettee nor Otis Pettee appear to have lived in the area by 1815. So the mystery of Charles Pettee remains.

Other than Fiske’s History of Wellesley, the earliest reference to a nail factory at Longfellow Pond comes from a deed dated January 1, 1816 from Ephraim Ware — owner of 303 Worcester Street as well as much of the land around the northern half of Longfellow Pond — to Benjamin Knights, a nailor from Newton. This isn’t to say that Charles Pettee didn’t manufacture nails there in 1815 or earlier — even the description of the one acre of land conveyed in this deed makes reference to an “old dam” — but we wonder why there isn’t any deed or lease from Ware to Pettee. Regardless, it appears that the nail factory was only in operation for a short time, as Knights sold the property back to Ware in 1817.

The next time any mill at Longfellow Pond appears in Town or County records is in 1825. This mill, however, manufactured paper instead of nails. Alas, just as with the nail factory, many of the details regarding the paper mill have been lost to history. But there are still enough to tell a story. So let’s break down what we know by using the five Ws and one H.

The who and when are by far the simplest to answer. Just take a look at the following list of the owners of the paper mill:

- 1825-1830: Charles & Thomas Rice

- 1830-1835: Henry F. Bartlett

- 1835-1836: Thomas Orr

- 1836: Isaac Keyes

- 1836-1847: Luther & Zenas Crane

- 1847-1868: Nathan Longfellow

It probably goes without saying that the pond was named for the last person on that list — Nathan Longfellow — although many people mistakenly think that the famous poet, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, was its namesake. (Coincidently, they were third cousins.)

And to be precise, it was actually known as Longfellow’s Pond up until the late 1910s and early 1920s, at which point the possessive form was dropped in favor of the pond’s current name. Certainly a better choice than going back to its original name — ‘the mill pond.’

We’re also able to determine with a fair degree of certainty why the paper mill was established. Just as the village of Upper Falls had become a leading supplier of nails, Lower Falls — specifically, Washington Street and lower Walnut Street — had developed by 1825 into one of the larger paper manufacturing centers in all of New England. Given that land and water rights were in extremely high demand, the old iron factory and dam at Longfellow Pond offered a perfect opportunity to establish yet another paper mill.

The first to do so were Charles Rice — already an owner of one of the paper mills in Lower Falls — and his brother, Thomas Rice — who would later acquire a separate paper mill in Lower Falls as well.

In addition, a third Rice brother would be affiliated with the paper mills, and so would two of Thomas’ sons. Given the close connection of the mills to the development of Lower Falls, as well as the involvement of the Rice family in pretty much all aspects of village life from the early 1800s until around the 1950s, it shouldn’t be surprising that the Rices were perhaps the most important family in the 300-year history of Lower Falls. Look closely and you’ll still see their presence there today: the two-story building which is occupied in part by Dunkin’ Donuts has its name — Rice Block — inscribed on its facade. And the family’s influence would even extend beyond Lower Falls — another son of Thomas Rice, Alexander Hamilton Rice, was Mayor of Boston from 1856-57 and Governor of Massachusetts from 1876-78.

It’s also worth saying something about the family of Luther and Zenas Crane, another pair of brothers who got their start in the paper mills in Lower Falls before operating the one at Longfellow Pond. In particular, their uncle — also named Zenas Crane — founded Crane & Co. in 1801 along the Housatonic River in Dalton, Massachusetts (which remains to this day the leading supplier of paper used to make United States currency). In fact, before heading out to western Massachusetts, Zenas Crane (the elder) had first learned the paper-making trade in Lower Falls.

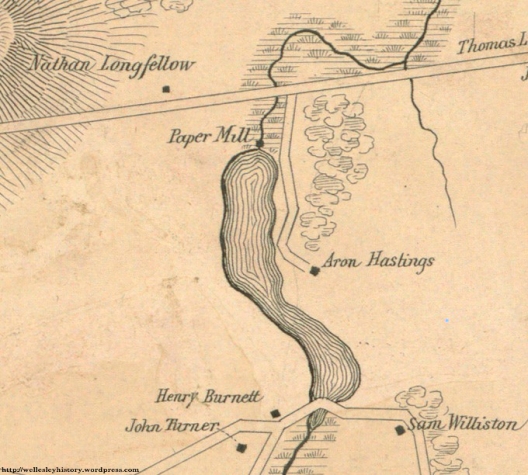

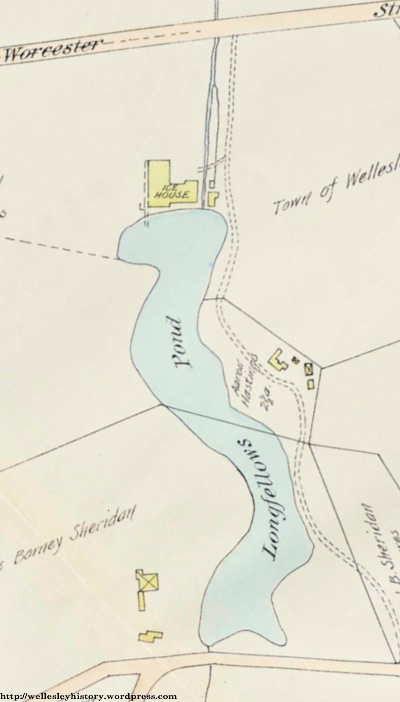

As to where exactly the paper mill at Longfellow Pond was located, we wish this was the easy part — after all, we know from maps and deeds that the mill was located near where the dam is currently located.

Unfortunately, there’s no map, image, or text that gives us a precise description of where the mill building sat. The only evidence comes from the old conglomerate-like foundations around the brook at the north end of Longfellow Pond. Although much of it is missing in certain areas, the remaining pieces of the foundation seem to suggest that whatever mill was once there was not simply some shack. Rather, it was a more elaborate structure that was built over the dam and then extended along the eastern side of the brook. (There may also have been more than one building.)

There is, of course, one building affiliated with the paper mill that is still standing today. And that’s 303 Worcester Street. Built in 1790 by the aforementioned Ephraim Ware, the house also served as the residence of mill owners Isaac Keyes and Nathan Longfellow. That shouldn’t be surprising given its close proximity to the pond.

303 Worcester Street in 1910 and 2013

(Left: Posted with permission from the Schlesinger Library, Radcliffe Institute, Harvard University)

(Right: Photo taken by Tycho McManus in August 2013)

That leaves just the what — what did they make? — and the how — how did they make it? OK, we know they made paper. But what kind of paper? Well, again, not a whole lot is known about the products that were manufactured there. All we can say is that the Crane brothers made paper (lamp) shades and Longfellow manufactured “paper hangings” (i.e., wallpaper).

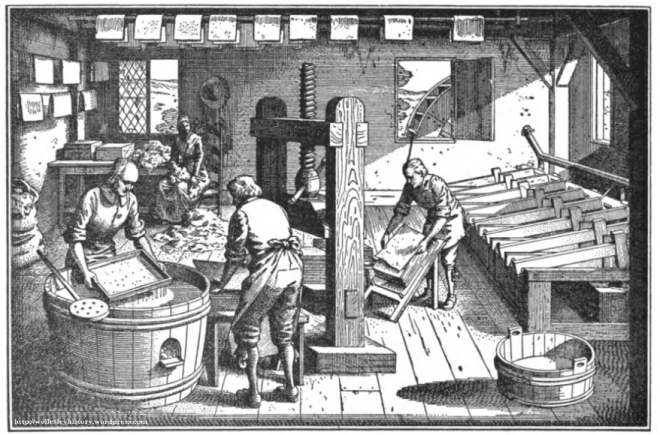

As for how they made it, that’s just one big question mark. There are absolutely no details whatsoever regarding the inner workings of the paper mill at Longfellow Pond. That said, we know a lot about the paper mills at Lower Falls. It’s therefore probable — given that the Rice and Crane brothers worked at both sites — that whatever was going on at Longfellow Pond was just done on a much smaller scale.

So it’s highly likely that the first step at the Longfellow Pond paper mill would have been the shredding of used linen or cotton rags and clothing. (This was, after all, before the advent of wood pulp paper.) This part of the papermaking process was actually one of the main reasons the mill needed to be adjacent to the dam — falling water would power a hollander beater that literally beat the cloth rags into a watery pulp.

The other part of papermaking was the actual making of paper. That meant — at least during the earliest years of the mill — that workers collected the pulp on a screen, compressed it using a vice-like machine, and then hung the sheet to dry.

However, by the 1840s and 1850s — when the Crane brothers and Nathan Longfellow operated the mill — paper-making technology had advanced to the point where instead of manufacturing the paper by hand, the mill workers simply oversaw a complex machine that consisted of two main parts: (i) a large cylinder with wire mesh sides that was rotated while half submerged in a vat of watery pulp and (ii) a conveyor belt that fed the screened pulp into a compress. Unlike manufacturing paper by hand, this machine produced long sheets of paper which could then be dyed, patterned, and cut.

Well, whatever equipment was at the paper mill at Longfellow Pond was lost when the structure burned down in 1868. At that point, Nathan Longfellow had enough with manufacturing and chose not to rebuild the mill. Instead, he spent the remainder of his life tending to his farm. (Longfellow — a Bowdoin graduate who spent nine years as a teacher in Georgia before moving to Wellesley — also kept himself busy by serving on the Needham School Committee for nearly 25 years between 1845 and 1875.)

So that marks the end of the story about the paper mill. But we aren’t even close to finishing our discussion on the history of industry at Longfellow Pond. In fact, there’s an entire second chapter involving ice harvesting. So why don’t we use the five Ws and one H to break down this subject as well?

This time, let’s start with the what and why because they’re really quite simple: ice was harvested from the pond each winter because people needed it to keep their meats and dairy from spoiling during the warmer months.

The how is also pretty straightforward. At several times each winter, after the ice on the pond was thick enough (usually about 10 inches or so), workers walked out onto the frozen pond and — with the help of horses — cleared it of snow and cut out large sheets of ice which were then further reduced into small blocks. The men then pried those blocks out with long-handled chisels and dragged them along a channel of open water to a long conveyor belt which sent the ice onto land and up and into a large storage house — the so-called “ice house” — where it was stacked neatly and covered with sawdust (which would prevent the ice from melting). Ice dealers then transported the blocks to customers either by horse-drawn cart or, starting in 1912, by truck.

If that description wasn’t clear enough, how about a video showing the ice harvesting process? (Note that the movie below shows Stillwater Lake — a reservoir that covers 315-acres in the Poconos — which was way larger than Longfellow Pond. Ice harvesting at both sites, however, was very similar.)

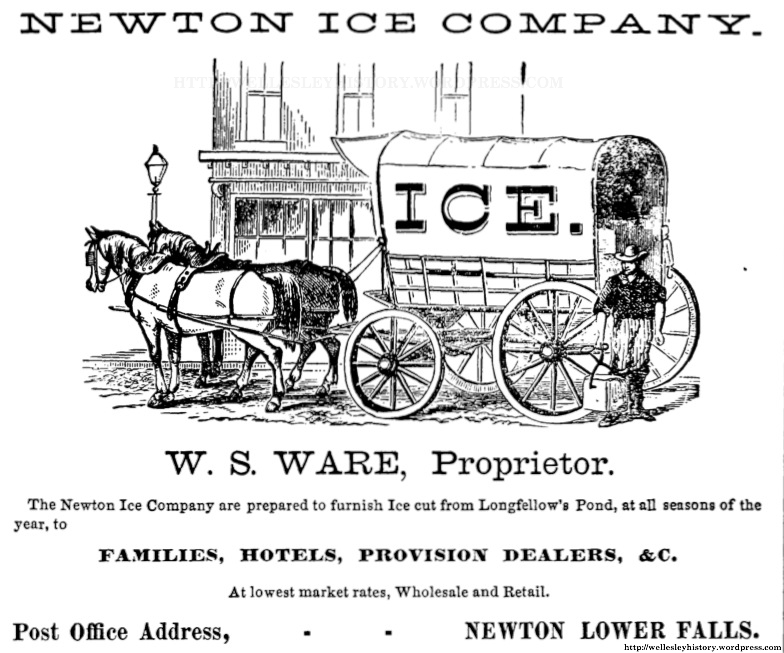

As for the who and when, it all started in 1869 — the year after Nathan Longfellow’s paper mill burned down — when he leased the property at the northern end of the pond to Asa H. Jones — an ice dealer — and Charles H. Hyde — a grocer in Newton Lower Falls (in the building now occupied by Lower Falls Wine Co.). Together, Jones and Hyde started the Newton Ice Company. But they wouldn’t run the business for long. In fact, the Newton Ice Company had no less than six different groups of proprietors during its first fifty years in operation.

By 1925, the Newton Ice Company had been taken over by the Metropolitan Ice Company, a larger business that harvested ice on several ponds throughout the suburbs of Boston. (There were also at least two other waterbodies in town that were used for ice harvesting: (i) the Diehl’s pond on Linden Street on the current site of Roche Bros. and (ii) Morses Pond which was operated by the Boston Ice Company.)

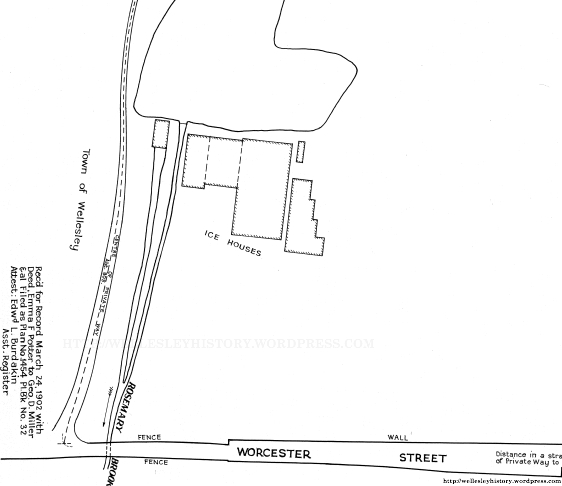

So where were the ice houses located on the land surrounding Longfellow Pond? Well, there were actually two different locations. Before 1923, the ice houses sat right at the north edge of the pond (more or less on the current site of Ollie Turner Park).

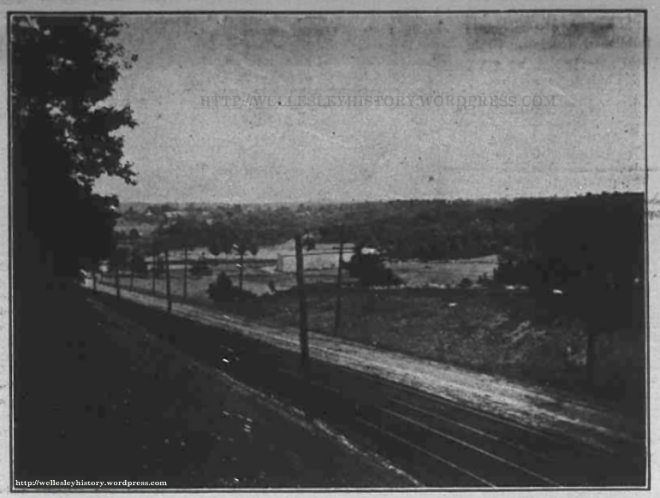

In fact, we actually found a photo — albeit, one that isn’t very clear — that shows these ice houses around 1903.

Photograph of the ice houses at Longfellow Pond (circa 1903)

(Posted with permission from the Wellesley Townsman)

Just for reference, this photo was taken standing on the old Worcester Turnpike (the carriage lane) at Longfellow Road looking southeast. You see the new Worcester Street in the foreground, along with two sets of trolley tracks for the Boston & Worcester Street Railway separating the eastbound and westbound lanes. Today, much of the land on the opposite side of Worcester Street is now either forested or part of the eastern end of the Standish Estates (i.e., Carver, Dudley, and Winslow Roads).

Unfortunately, the ice houses shown in the photo burned down in 1923. But here’s a photo of what we think are the remains of one of their foundations (located in the woods to the west of the dam):

A new 32’x113’ icehouse was then built to the west of the northern end of the Longfellow Pond on the current site of Dudley Road. It’s believed that the concrete piers that stick out of the pond are remnants of the ramp that led to this second icehouse. There are also three concrete posts nearby that were probably part an old fence that once marked a path that led down to the pond.

It’s not precisely known when ice harvesting on Longfellow Pond stopped, but the records seem to suggest it was around the late 1920s. Not very surprising, considering that by then most people in Wellesley and the surrounding towns already had their own electric refrigerators. But there were still some who either preferred the old-fashioned icebox or could not afford a new fridge. So the Metropolitan Ice Company continued to store ice there from other lakes and ponds up until the early 1940s (at which point the ice house was briefly used as a rifle range by the Massachusetts Guard). It appears then that the ice house sat vacant until it was razed sometime after 1947 but before 1950 (when Dudley Road was laid out).

So that’s it for the story about industry at Longfellow Pond. Well, actually, we failed to mention one other industrial activity that took place there. Starting in 1881, Nathan Longfellow leased the use of the dam to the Waste Recovery Company, a business that we know nothing about. But it certainly doesn’t sound very environmentally friendly. And by 1885, the dam had been taken over by a wool cleansing business. Not exactly something you wanted right next to where your ice was produced.

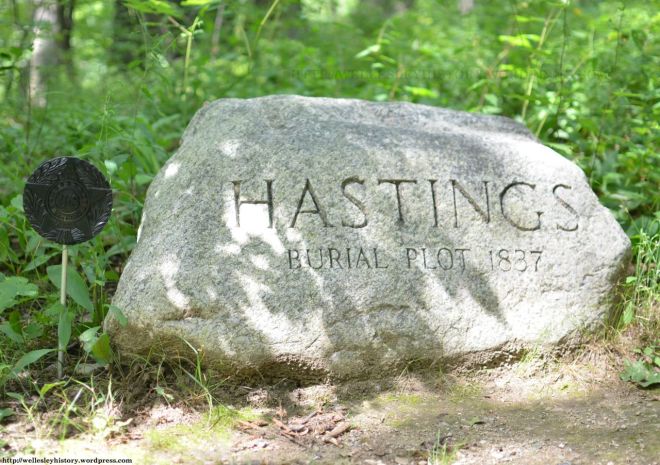

But we’re still not done yet! There’s one more subject that needs to be discussed: What’s the deal with the Hastings family burial plot on the eastern side of the pond?

It’s almost impossible to imagine today, but the wooded area around the grave marker was once a small 2 ¾ acre farm that was occupied by the Hastings family for nearly a century, from 1837 — hence the date on the boulder — until 1930.

To be honest, there isn’t a whole lot that people will find interesting about the Hastings family. It was just Aaron Hastings — a simple yeoman — and his wife, Eliza, along with their children, John and Sarah (and an adopted orphan, Richard Cunningham).

Besides John Hastings — who was a handyman and did some work filing saw blades and cutting wood for the Newton Ice Company in his later years — the Hastings family had little to no affiliation with the industries at Longfellow Pond despite their close proximity. They either just worked on their farm or found manufacturing jobs elsewhere.

(Richard Cunningham was, however, a notable exception. For unknown reasons — perhaps he was gifted at school or just enjoyed business — Cunningham left the Hastings house at the age of fourteen to enter into the leather trade, eventually becoming successful enough to establish his own firm in Boston. And locally, he was known as one of Wellesley’s most involved citizens, serving as a member of the Board of Selectmen for thirteen years and as Assessor for over two decades.)

The precise date that the Hastings house was removed is unknown. Our best guess is the mid-1940s, long after the death in 1930 of its last occupant, 84-year-old John Hastings (who was found by Cunningham on verge of death, lying in bed suffering from pneumonia in the unheated house during the heart of winter).

Today, all of the farmland and pasture that once surrounded the house is completely covered with large trees and overgrowth. But if you hack your way through the forest and dig through the leaves and detritus, you’ll find a few relics of the old Hastings homestead:

There are also the vestiges of Rosemary Street — an old cart path connecting Worcester and Oakland Streets that was probably used almost exclusively by the Hastings. You can actually still walk on most of the northern end of Rosemary Street, which serves as the access road from Route 9 and as part of the walking trail around the pond. And even some of the southern section — which has been mostly abandoned — is still navigable in places:

And as for who’s buried in the Hastings burial plot, we have no idea. It’s definitely not John Hastings or his sister, Sarah — whose graves are both located at the East Parish Burying Ground in Newton — but it could be their parents, Aaron and Eliza. (There’s a United States veteran marker next to the burial plot, but we think that was placed there mistakenly in honor of John Hastings, who was a member of Company K of the 42nd Regiment of the Massachusetts Infantry during the Civil War.)

It wasn’t until 1947 — seventeen years after the death of John Hastings — that the Town purchased the old Hastings farm (along with the abandoned property of the Metropolitan Ice Company) for the development of a recreational area. In particular, Town officials had been concerned that the post-war construction boom — which included much of the Standish and Sheridan Estates — would continue to eat up any and all undeveloped land, leaving behind few places in Wellesley where residents could enjoy the outdoors.

And they were right. Today, Longfellow Pond — along with Morses Pond, Lake Waban, and Boulder Brook Reservation — are perhaps the only spots in Wellesley that really make you forget about suburbia and force you to appreciate the natural world. Of course, now you know just how natural Longfellow Pond really is.

Sources:

- Norfolk County Registry of Deeds

- Federal Censuses of 1820, 1850, 1860, 1870, 1880, 1900, 1910

- 1856 Map of Needham by Henry Francis Walling

- Newton Directories: 1868-1934

- History of Newton, Massachusetts by Samuel Francis Smith (1880)

- The New England Historical and Genealogical Register, Volume 47 (1893)

- Dedham Historical Register, Volume 4 by the Dedham Historical Society (1893)

- 1897 Atlas of Wellesley by George W. Stadley & Co.

- Obituary Record of the Graduates of Bowdoin College and the Medical School of Maine (1899)

- Epitaphs from Graveyards in Wellesley by George Kuhn Clarke (1900)

- Crane, 1648-1902 (1902)

- Vital Records of Newton, Massachusetts, to the Year 1850 by the New England Historic Genealogical Society (1905)

- History and Genealogy of the Jewetts of America by Frederick Clarke Jewett (1908)

- Memorial Biographies of the New England Historic Genealogical Society, Towne Memorial Fund (1908)

- General Catalogue of Bowdoin College and the Medical School of Maine by Bowdoin College (1912)

- History of Needham, Massachusetts: 1711-1911 by George Kuhn Clarke (1912)

- Wellesley Townsman: 31 May 1912; 3 October 1913; 25 October 1918; 12 December 1919; 28 September 1923; 19 October 1923; 26 February 1926; 28 October 1927; 5 November 1929; 21 February 1930; 28 February 1930; 18 October 1935; 17 February 1939; 3 April 1941; 5 November 1942; 20 May 1943; 1 June 1945; 6 July 1945; 3 April 1947; 10 July 1947; 17 January 1952; 22 March 1956; 29 March 1956

- History of the Town of Wellesley, Massachusetts by Joseph E. Fiske (1917)

- One Hundred Years of Paper Making by Clarence Augustus Wiswall (1938)

- A Longfellow Genealogy by Russell Clare Farnham (2002)

- The Frozen Water Trade: How Ice From New England Lakes Kept the World Cool by Gavin Weightman (2003)

- Rag Paper Manufacture in the United States, 1801-1900 by A.J. Valente (2010)

- The Makers of the Mold: A History of Newton Upper Falls, Massachusetts by Kenneth W. Newcomb (accessed in September 2013)

- Interment.net — Old East Parish Burying Ground in Newton, Massachusetts (accessed in July 2013)

I do recall, in the early 1950’s, when I was maybe two or three years old, my parents had an ice delivery for the Ice Box. Even when we went Electric, my mother continued to call it the ice box for some time. Good work Josh, I like to re-read this for the tinier details. I believe my sister lived at 31 Columbia for a while. I will check for it when she is off of her vacation from a vacation.

Fantastic, In the 1960’s as an Eagle Scout conservation project we cleaned up the pond and stocked it with bass.

My brother recalls getting ice at the Longfellow ice house in 1936. Is this possible?

Yes, it’s certainly possible. Records seem to indicate that the ice house at Longfellow Pond was used for storing ice up until the late 1930s or very early 1940s. I don’t think, however, the ice came from the pond. Rather, it was shipped in by trucks from other ponds outside of Wellesley.

Pingback: The Week in Review (Day 44-47) – Charlie H. Sills

Pingback: A quick walk around Wellesley's Longfellow Pond - The Swellesley Report

Hi, I live in Natick and have started to look for local nature trails to walk on the weekends. I walked around Longfellow pond this morning. It’s a nice walk. I wish I had read this history before I walked it. Thank you writing it. It was very interesting. I will have to take the walk around it again now that I know more about it. Where can I find more of your writings?

Pingback: Wellesley hike: the trails were fragrant along Longfellow Pond - The Swellesley Report