Let’s start this post off with a little thought experiment. Pretend for a moment that you’re the CEO of a company that manufactures and sells widgets. For years, everything was hunky-dory. Profits were high and the future always looked strong. But lately, demand for your widgets has decreased significantly and your business is hemorrhaging money. It’s obvious you need to do something.

So as CEO, what should you do to turn your company around? Perhaps reinvent your product? Invest in a new marketing campaign? Restructure your operations to improve efficiency and reduce costs?

Makes sense? It’s called Business 101.

Now, what’s the 100% wrong approach to take? How about sticking with the same old strategy and even spending millions of dollars to construct a second factory that manufactures identical widgets as the ones that aren’t selling? That basically guarantees failure, right?

Well, that’s pretty much what the financially-strapped Archdiocese of Boston did in the mid-1960s when it spent $5.5 million to construct a new high school building for the Academy of the Assumption in Wellesley (now the site of Mass Bay Community College) and a new Formation Center for the Sisters of Charity of Halifax (currently used as the Elizabeth Seton Residence) on the opposite side of the road adjacent to what is now Centennial Park.

I think I’m justified in saying that this was a pretty dumb move. Although the Academy desperately needed a new high school, things were changing within the Catholic Church. Yes, membership was still strong. But it was more or less at that time — the early-to-mid-1960s — that the number of women entering Sisterhood peaked. Furthermore, fewer and fewer of these religious sisters were becoming teachers.

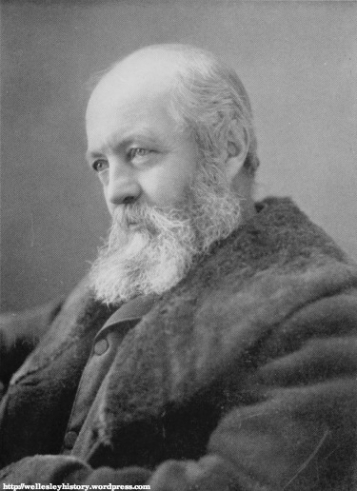

None of those facts were unknown to Church officials. Even the Archbishop of Boston, Richard Cushing, spoke solemnly about the future of the Catholic Church at the dedication ceremony for the new high school.

Let me repeat that: The guy in charge of the entire Archdiocese was openly worried even as he marked the completion of a high school that had been constructed for $2 million (through loans). And then he goes ahead and authorizes the expenditure of $3.5 million (again, using money the Church hadn’t raised yet) to establish a Formation Center that would hopefully increase the number of young women entering the Sisterhood.

Did Cardinal Cushing and other Church officials really think that the only problem was a lack of training and educational services? Was it not obvious to everyone that society was in the midst of radical changes and that the best way to survive was to adapt to them?

OK, perhaps I’m getting ahead of myself. Some of you might have no idea what I’m talking about. Who were these Sisters of Charity of Halifax? And how in the world did they end up in Wellesley?

The short answer: The Sisters of Charity of Halifax were a group of women from a congregation in Halifax, Nova Scotia who were sent on a mission in the late 19th Century to establish a school for young women in the Boston area.

The long answer: Please fasten your seatbelts. We’re going for a ride!

Let’s start this off more than two centuries ago, all the way back in 1803. But not in Wellesley or even Canada. Nope, Italy marks ground zero for this story. After all, it was here that Elizabeth Ann (Bayley) Seton first discovered Catholicism.

I’ll spare you the full biography of Elizabeth Seton, but there’s a certain amount of information that we can’t ignore. Like the fact that she was born into a prominent and deeply Protestant family in New York City. And that, as a wife and mother of five young children living in Manhattan, Elizabeth found herself in an unforeseen situation when her husband, William Seton, contracted a serious case of tuberculosis that was so unresponsive to the most advanced medical treatments of the time that his doctors prescribed a sea voyage to Europe as a last resort to revive his health.

Unfortunately, it only got worse when Elizabeth and William (along with one of their children) stepped off the boat in Livorno, Italy. Rather than resting at a mountainside villa, the family was immediately quarantined in a lazaretto for a month — not for tuberculosis, but because there was a yellow fever epidemic in New York and Italian officials believed that their ship was contaminated. Unable to receive the care he needed, William died only a week after his release.

One would think that his death would send Elizabeth’s life into despair. But this didn’t happen. On the contrary, she showed an absolutely remarkable amount of strength and fortitude even despite having to wait three months to sail home due to rough seas.

There must, however, have been at least some yearning for solace because it was at this precise time that Elizabeth first discovered the Catholic faith. (Remember, America was almost entirely Protestant at the time.)

In fact, she even writes about this moment in a letter to her sister:

“Four days I have been at Florence, lodged in the famous palace of Medici [where she was living with the family of Anthony Filicchi, one of her late husband’s creditors]…On Sunday, January 8, at 11 o’clock, I went with Mrs. Amabilia [the wife of Anthony Filicchi] to the chapel La Santissima Annuziata. Passing through a curtain, my eye was struck with hundreds of persons kneeling; but the gloom of the chapel, which is lighted only by the wax tapers on the altar, and a small window at the top darkened with green silk, made every object at first appear very indistinct, while that kind of soft and distant music which lifts the mind to a foretaste of heavenly pleasures called up in an instant every dear and tender idea of my soul, and, forgetting Mrs. A.’s company and all the surrounding scene, I sank on my knees in the first place I found vacant, and shed a torrent of tears at the recollection of how long I had been a stranger in the house of my God, and the accumulated sorrow that had separated me from it.” — White (1880)

Fully convinced in the power of Catholicism, Elizabeth immediately renounced her Anglican religion upon returning home to New York and accepted a self-imposed mission to spread her newfound faith throughout America.

Of course, there was one huge problem:

Appealing as she must have been in her courage, her confidence in God, and her faith in their guidance, she was, nevertheless, greatly handicapped. What apostolic work could reasonably be expected of a young widow, a convert of a few months, who would be responsible for many years to come for five children ranging at this decisive moment from the ages of ten to two? And yet there seems to have been no doubt in the minds of these great missionaries that Elizabeth Seton had been called by God to do a great work in the Catholic Church. — Walsh (1960)

Her initial assignment: to take charge of a small religious girls’ school located in a five-room house in Baltimore. (This city had only months earlier, in April 1808, become the first Archdiocese in the United States.) It was here that the foundations were laid for what would become the Sisters of Charity, the first congregation of religious sisters in this country.

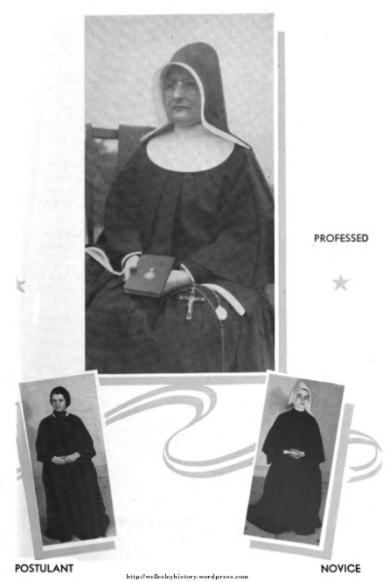

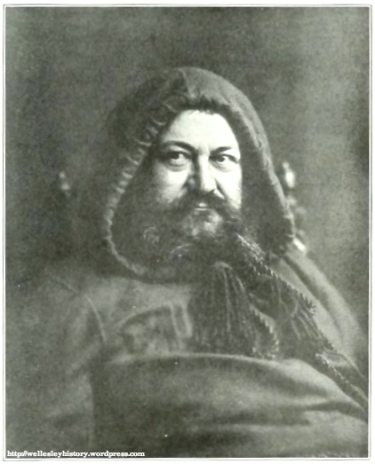

It was also here that Elizabeth and several of her students wore for the first time the standard outfit of the Sisters of Charity. Modeled after the clothes worn by Elizabeth during her widowhood, it consisted of a black dress, a black cape, and a white muslin cap with a wide crimped border that was tied under the chin. (The white cap was later substituted for a black one.)

Her school quickly grew to the point where they needed more space, so in 1809, Elizabeth attained the support of a wealthy Catholic convert to construct a motherhouse at Emmitsburg, forty miles northwest of Baltimore where Mount St. Mary’s College — the second Catholic university in the United States — had opened only a few months earlier.

This newly formed congregation — which was led by Elizabeth, who was now known affectionately as ‘Mother Seton’ — took on the name ‘The Sisters of St. Joseph’s’ and dedicated itself to the education of young women. (According to a rule established by St. Vincent de Paul for his Daughters of Charity in 17th Century France, all active groups of sisters must be dedicated to a particular cause.)

St. Joseph’s Academy opened in Emmitsburg in February 1810 with immediate success. And as the school grew, so did the motherhouse. Within a short time, groups of sisters were sent on missions in other cities throughout the Eastern United States.

In 1846, one of those offshoots established its own congregation, the Sisters of Charity of New York. It was of this group that the Bishop of Halifax, who was struggling to spread Catholicism within Eastern Canada, requested help. So four sisters traveled north of the border in 1849 to open yet another parochial school for girls. Seven years later, a motherhouse and novitiate were constructed in Halifax. The Sisters of Charity of Halifax was thus born.

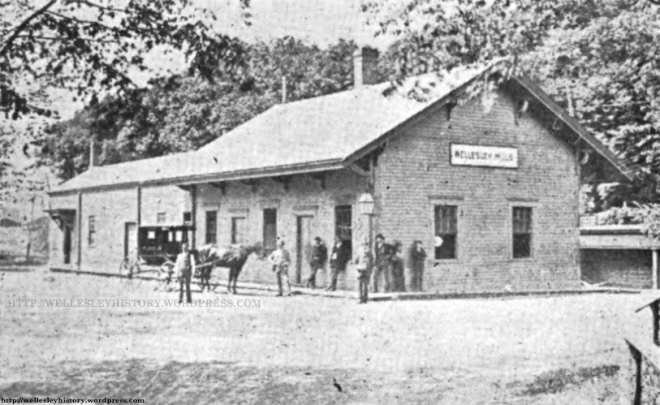

That leads us back to Wellesley. (Thank God!) Just as each of the other congregations sent groups of sisters on far away missions, so did the Sisters of Charity of Halifax. One of those missions began in 1887, when seven sisters traveled to Boston to establish St. Patrick’s School in Roxbury. And six years later, given the success of the Roxbury school as well as the continued growth of the girls’ academy at Halifax — which was drawing students from as far away as the Arizona Territory — it was proposed by the Church officials to establish yet another, even larger school in the Boston area.

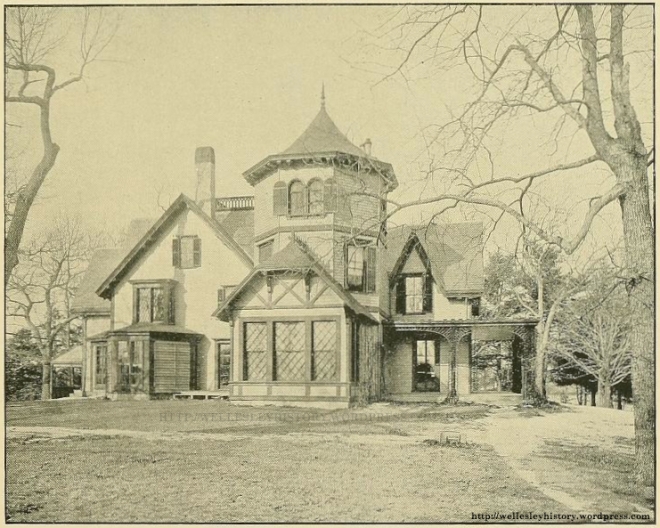

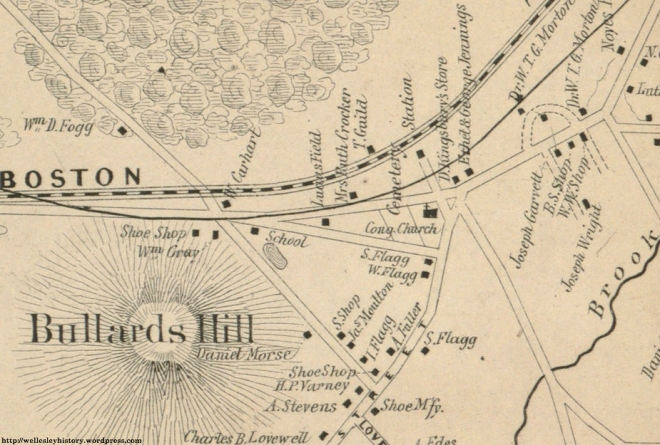

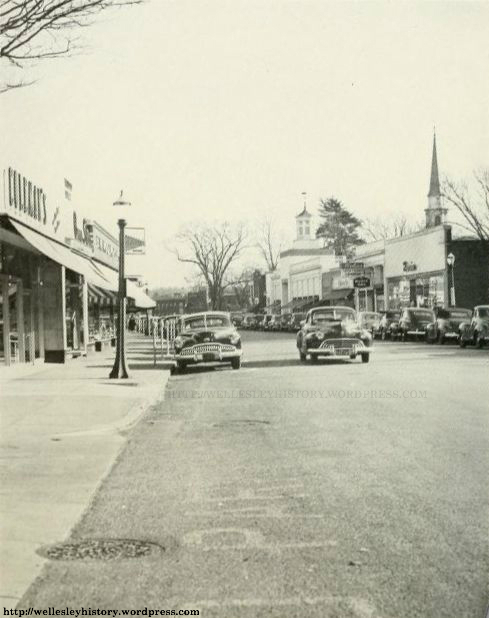

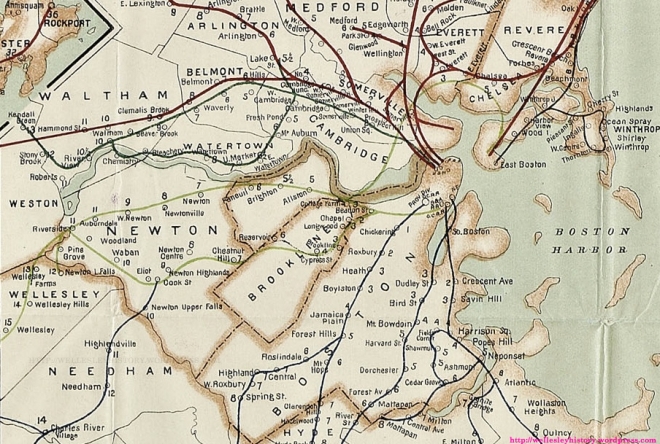

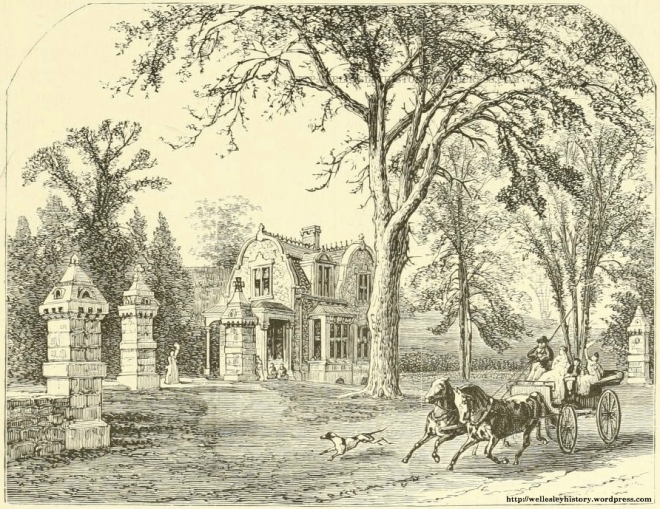

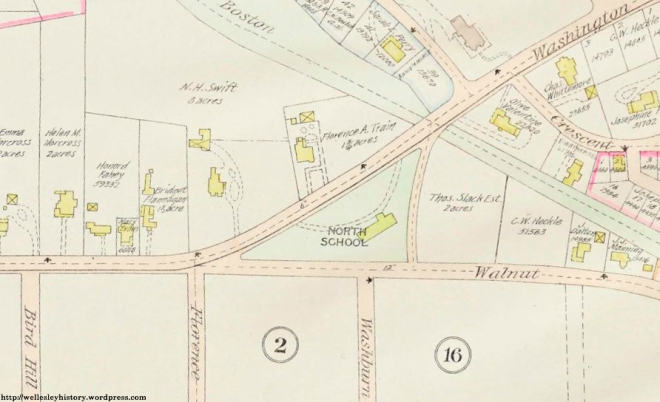

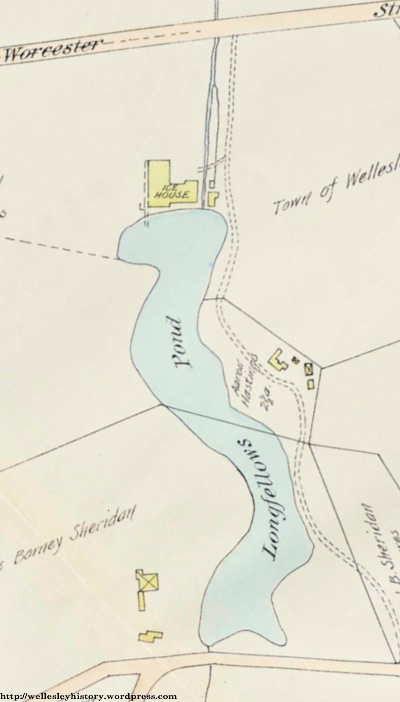

Following a tour of several sites within the suburbs of Boston by the Mother Superior of the Halifax congregation, they settled on the 154-acre Bird-Scudder Estate in Wellesley Hills.

The estate itself consisted of four separate houses, the largest of which was the former Bird-Scudder mansion. Constructed around 1830 by John S. Bird, a wealthy farmer and land owner, this farmhouse was sold in 1848 to Marshall Sears Scudder, an executive for a leading manufacturer of metal valves and pipes in Boston, who greatly enlarged it and embellished the structure with Italianate and Victorian-era detailing. He even reportedly installed the first bathtub in Wellesley!

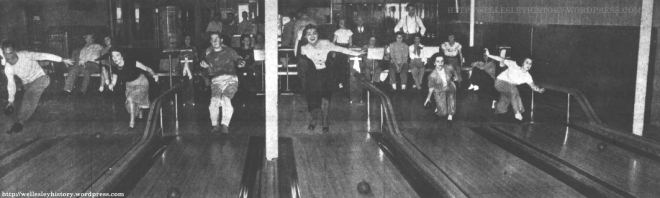

In addition to this mansion and the other three houses, this estate also included a carriage house, several barns, a greenhouse, six henhouses, a windmill, and even a bowling alley at the time the Sisters of Charity purchased it.

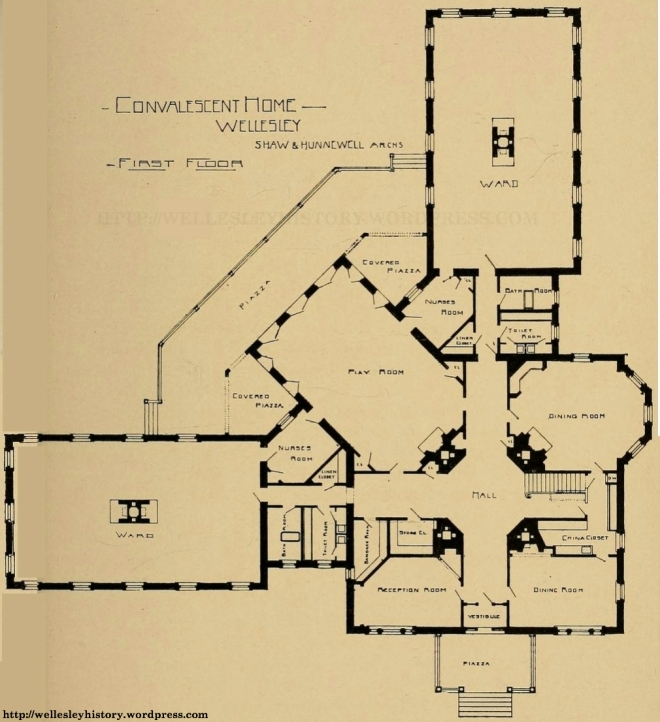

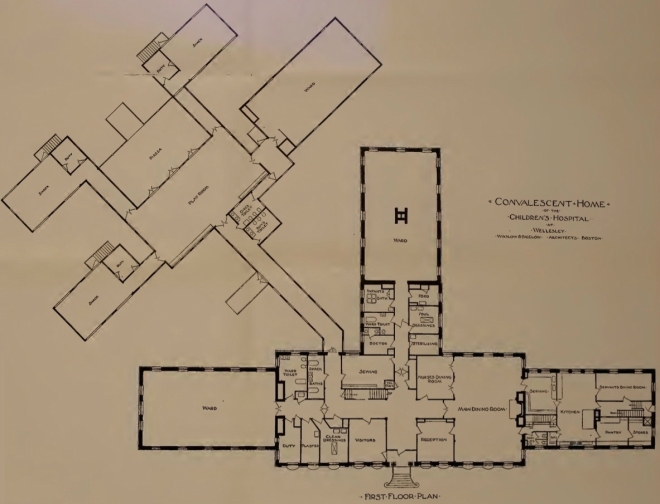

It may be of interest to note that immediately prior to the acquisition of the estate by the Sisters of Charity, a prominent doctor in the Boston area, Charles Cullis, had plans to relocate four separate hospitals he operated to this property: a consumptives’ home for the poor, a spinal home for women, a cancer home, and an orphanage for the children of his patients. Town officials, however, would not grant the appropriate permits to establish such a facility there, as “…they feared the name of their town, which had heretofore been known as healthful, might suffer by the introduction of this new venture.” The property was therefore made available to the Sisters of Charity.

But how did Wellesley feel about the arrival of a group of nuns who intended to spread Catholicism throughout the region? After all, this was a small town composed almost entirely of Protestants (with the exception of Lower Falls, which was heavily Catholic due to the large immigrant population working in the mills). Apparently, locals weren’t thrilled as the Sisters initially felt a “strong anti-Catholic prejudice” from the community. Fortunately, these feelings eventually dissipated.

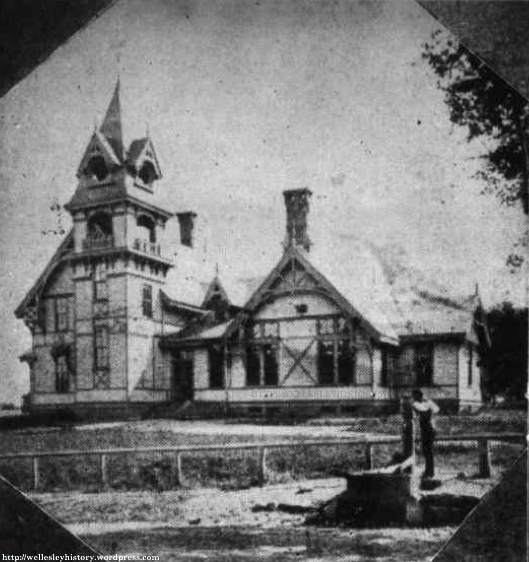

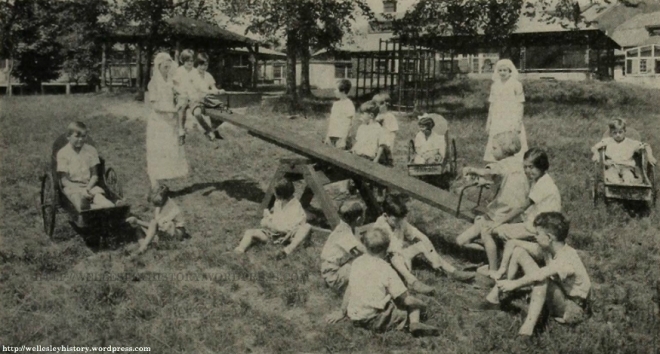

The Academy of the Assumption opened its doors to students in December 1893. At first only girls were accepted into the academy, but the following year, a separate preparatory school for boys ranging in age from 5 to 14 years — known as St. Joseph’s Academy — was constructed at the southern edge of the property.

To get an idea of the institution during its earliest days, check out the following description written by a visitor to the campus in 1897:

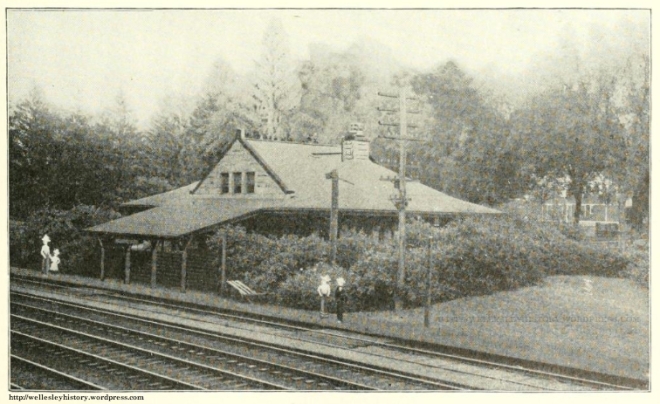

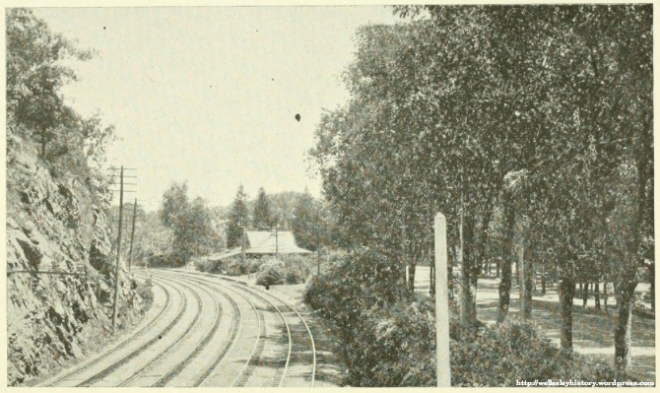

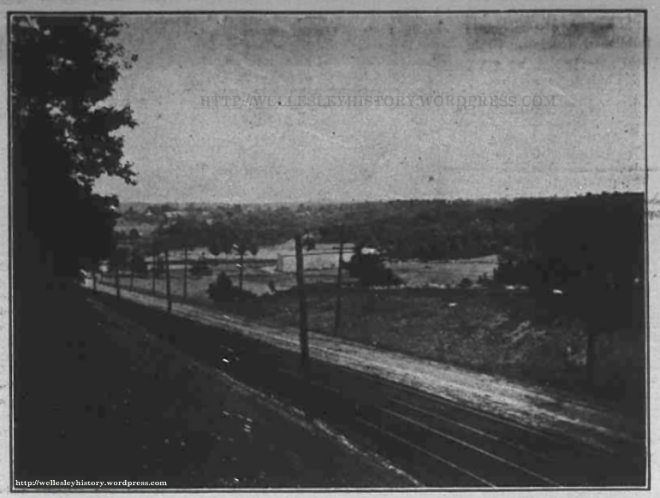

In looking through the various papers for an educational establishment that would meet my requirements, I saw in the columns of your valuable journal the advertisement of the Academy of the Assumption, Wellesley Hills, situated on the Boston & Albany railway, only a few miles from this city. As it is comparatively a new institution, a description of its works may prove interesting to your readers.

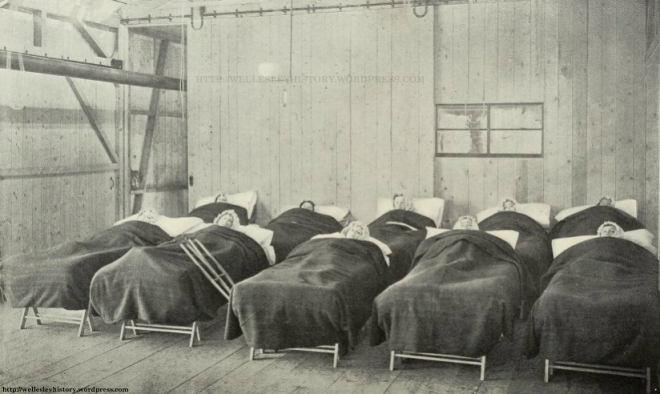

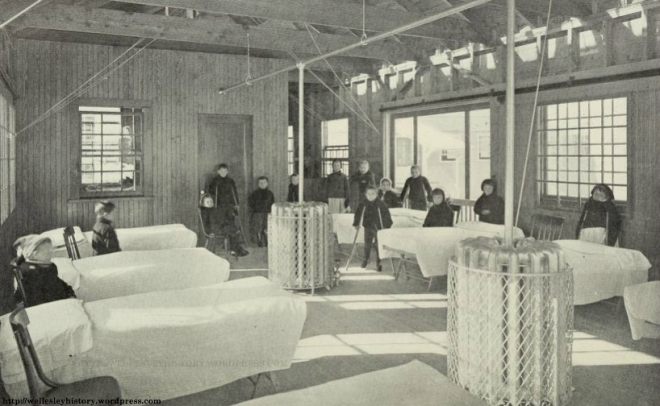

The Academy of the Assumption is conducted by the Seton Sisters of Charity, whose mother-house is in Nova Scotia. Some four or five years ago the magnificent estate of the late Dr. Cullis at Wellesley Hills, consisting of several hundred acres of land in a high state of cultivation, was purchased by the Sisters, who immediately opened at one end of the extensive grounds an academy for young ladies, and at the other a preparatory school for boys from five to fourteen years of age. Here the little fellows are cared for with maternal solicitude and affection, several of those at present there having been deprived of their own mothers by death. Here they are prepared for First Communion, taught to serve Mass and Benediction in the pretty convent chapel, where they assist at the Holy Sacrifice every morning, and at the same time they receive an education which fits them for entering college.

Some ten or twelve little fellows are spending their vacation at school, and they proudly showed us the flower-beds of their own planting and the extensive playgrounds where they seemed to be, like all boys, endowed with perpetual motion, and I sighed involuntarily as I thought of the poor Sister who would have to repair stockings and knickerbockers when the day’s sport was over.

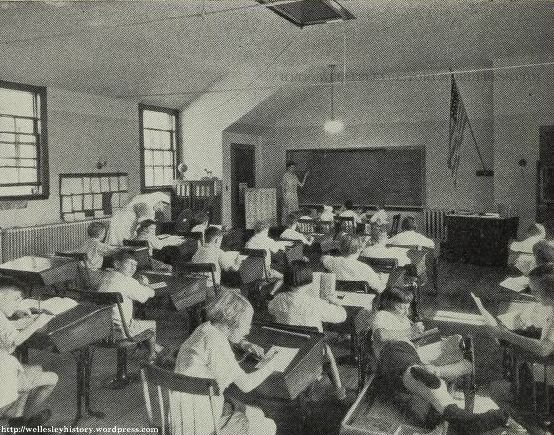

Walking through charming lawns, dotted by magnificent trees, we came to the handsome new academy for young ladies. It is built at the rear of the old gabled house near the entrance to the grounds, and is certainly a handsome edifice, constructed in the style of a French château, the upper stories being finished outside in oiled wood. This building contains spacious classrooms, recreation and music halls, studios, dormitories, laundry, baths, etc., fitted up with all modern conveniences, and lighted throughout by electricity. Here are taught music — vocal and instrumental — painting, drawing from casts, plain and fancy needlework, domestic economy, and all the branches of a literary and scientific education.

Ample lawns have been left as recreation grounds, while the many broad acres under cultivation yield plenty of fresh vegetables, so nutritious an accompaniment to the diet of growing children; a number of poultry-yards and some twenty cows give evidence of abundance of eggs and milk, and the beautiful fresh air, at an elevation of two hundred feet above the sea affords Wellesley greater natural advantages than the majority of our institutions can boast.

One more item took my fancy. My visit was made on the glorious Fourth — or rather Fifth — and two “star-spangled banners” floated to the breeze from the gables of Wellesley. “So,” thought I, “besides all other advantages the Academy of the Assumption is an American institution!” — The Sacred Heart Review, August 7th, 1897

Needless to say, the school — just like the other academies established by the Sisters of Charity — was an immediate success. By 1898, there were 63 students. Three years later, enrollment was up to 79. This trend continued for decades.

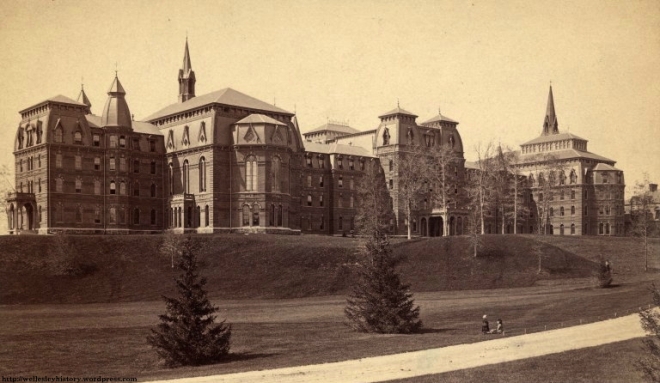

As the enrollment grew, so did the need for space. Initially, this mostly meant adding onto the existing buildings. But in 1920, they commissioned renowned architect, Franz Joseph Untersee, to design a massive English Gothic edifice that would give no visitor — or passerby on Worcester Street — any doubt that this campus was home to a prestigious academic institution.

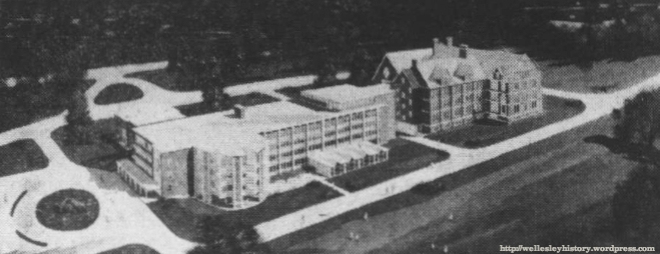

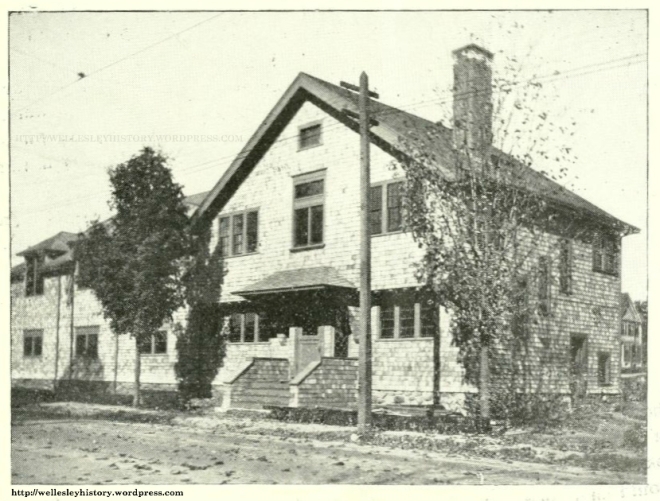

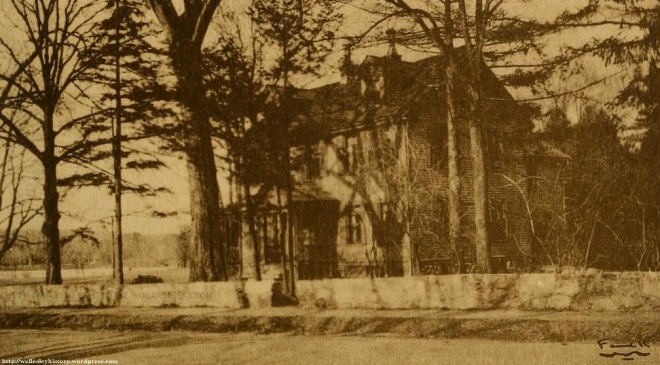

Main building and Bird-Scudder mansion (viewed from the eastern edge of the campus)

Source: 1931 Semi-Centennial Booklet

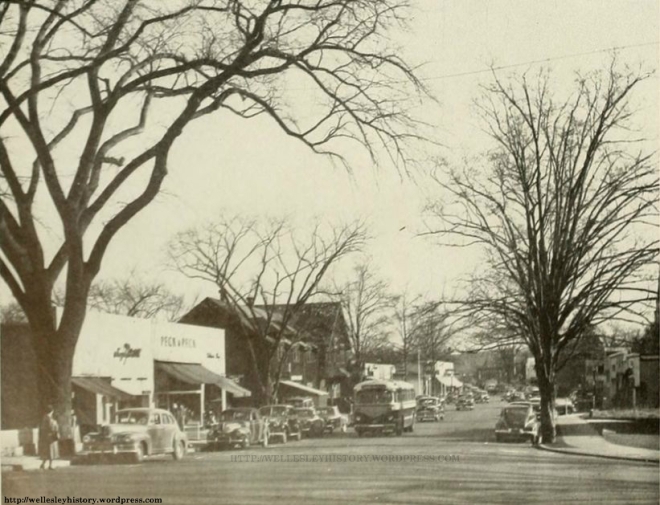

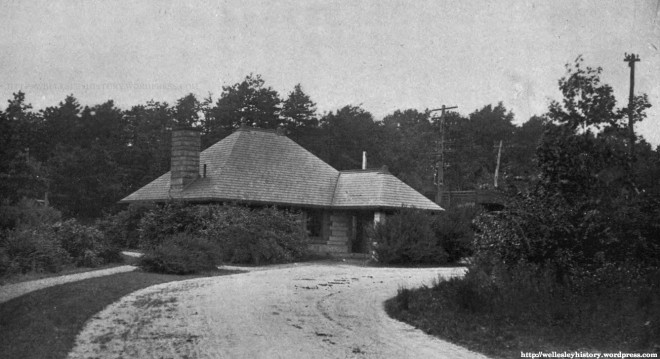

It appears likely that soon after this building opened in 1921, upon realizing the advantages of having an attractive campus that was visible from a major roadway, the Academy constructed the charming stone lodge that still stands at the intersection of Worcester and Oakland Streets. Beyond serving as a marketing ploy, this lodge provided shelter to students and staff who were waiting for trolleys on the Boston & Worcester Street Railway line.

Stone Lodge at corner of Worcester and Oakland Streets

(Originally located at street level — moved when Worcester Street became a state highway in 1932-33)

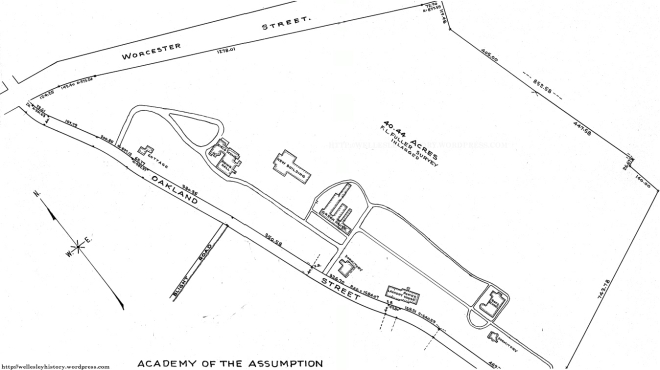

Walk through that lodge and the following campus awaited you:

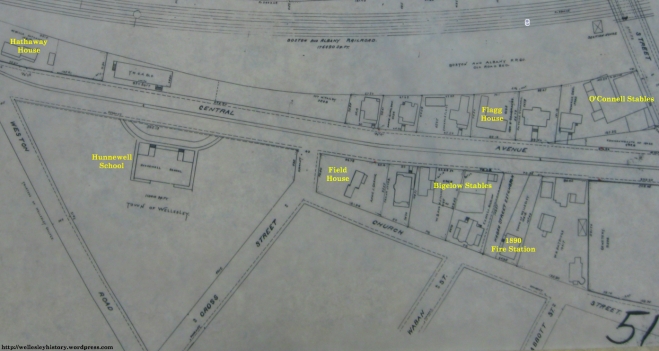

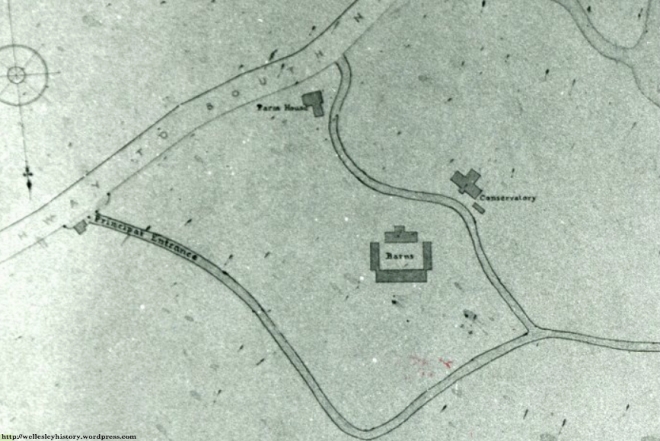

Map of campus in 1922 (prior to construction of stone lodge) — CLICK TO ENLARGE

Source: Norfolk County Registry of Deeds

As you can see, the only structures on the map that remain standing today are the ‘New Building’ and the ‘Laundry – Powerhouse’ building.

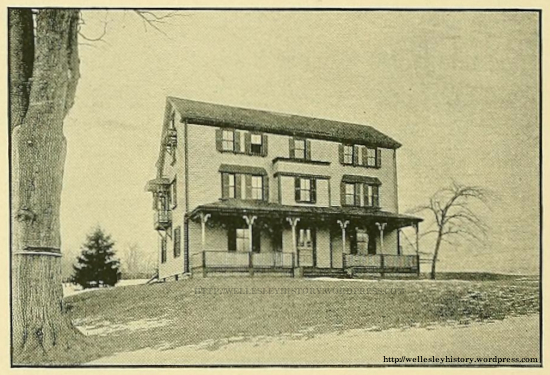

But there’s one other building from the Academy’s original campus that still stands and isn’t shown on this map: the Putney farmhouse. Located on the Academy’s 40-acre farm that it acquired the year after its purchase of the Bird-Scudder Estate (and included much of what is now the northeastern section of Wellesley Country Club’s golf course), this farmhouse served as the living quarters for the farmhands who grew the vegetables, milked the cows, fed the pigs, and collected the eggs that would end up on the plates of the hundreds of students and staff at the Academy.

So now that we’ve described the campus, what kinds of students went to the Academy of the Assumption and St. Joseph’s Academy?

From the beginning, both schools (obviously) catered towards Catholic children living within the region. Many were from Boston. And most were relatively poor children of immigrants primarily from Ireland, Italy, and Canada. The academies therefore offered not just a superior education but also a stable living situation for these children.

Not all students, however, fit that profile. Some of them came from more affluent Catholic families, most notably Dorothy Ruth, one of Babe Ruth’s adopted daughters who attended the Academy of the Assumption during the late 1920s when the Great Bambino was playing for the New York Yankees. (He even occasionally came to Wellesley to pick her up — an event that was understandably of great excitement to the townspeople.)

Nor were all students Catholic. In fact, many Protestant children from the surrounding area, including Wellesley, attended as day students.

As the years passed by, the Academy of the Assumption continued to grow, attracting more and more students from both Wellesley and far away places (including a whole bunch from Latin America). But in many ways, it was quite similar to most other religious schools in the region. The academy wasn’t even outrageously different from the other private schools in Wellesley.

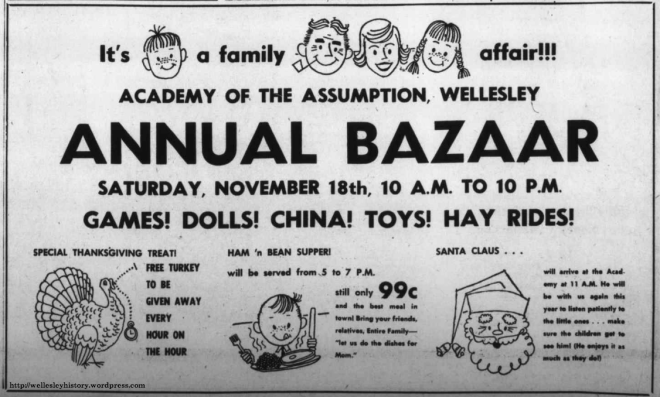

There were two annual traditions, however, that helped the school stand out within the community: the Christmas Bazaar and Field Day.

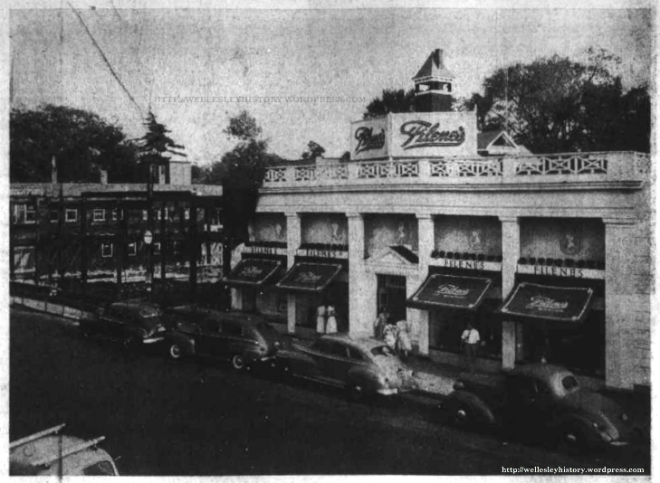

The Christmas Bazaar was exactly what it sounds like: an all-day bazaar that was held a month or so before Christmas where patrons could buy handmade gifts, needlework, toys, and religious articles. And each year, it became a larger and larger event with the addition of movies, games, lots of food, and even an appearance by Santa Claus (who would fly in via helicopter instead of sleigh).

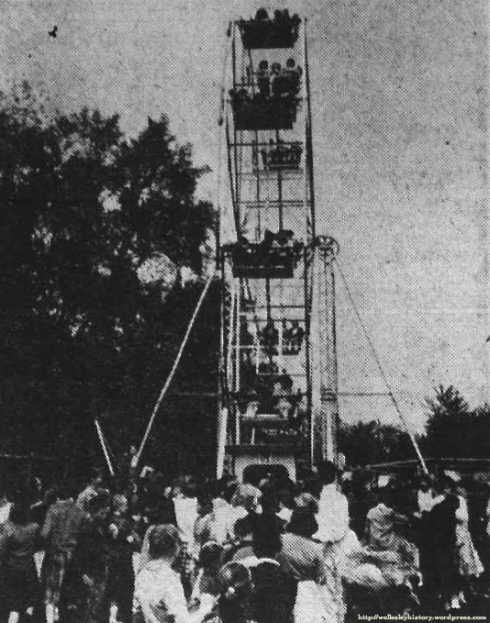

The other annual tradition — which was arguably even more exciting — was Field Day. First held in the 1910s, Field Day quickly evolved from what was more or less a pleasant social gathering into an all-out competitive sporting event where students from the Academy of the Assumption and St. Joseph’s would compete against students from other Catholic schools in various activities, including foot races, baseball games, horseback riding events, and even a military drill.

Its evolution would continue until Field Day had become a full-fledged carnival featuring rides, raffles, concerts, auctions, and all sorts of games. During the 1950s and 1960s, attendance each year reached upwards of five thousand.

Just as each Field Day was a resounding success, so was the Academy of the Assumption in general. Everything seemed to be looking great for the school. So much so that, once again, it needed more space and therefore constructed a large addition off the main building that included an auditorium, gymnasium, assembly hall, and more high school classrooms.

But this new space proved inadequate only one decade later, and so the Academy broke ground in 1963 for a relatively huge high school building (to be named after Elizabeth Seton) that would help give the Catholic Church a prosperous future.

There was just one huge problem: fewer and fewer religious sisters were available to teach at the Academy. The only solution therefore was to hire (more expensive and probably not as religious) lay teachers to fill open positions.

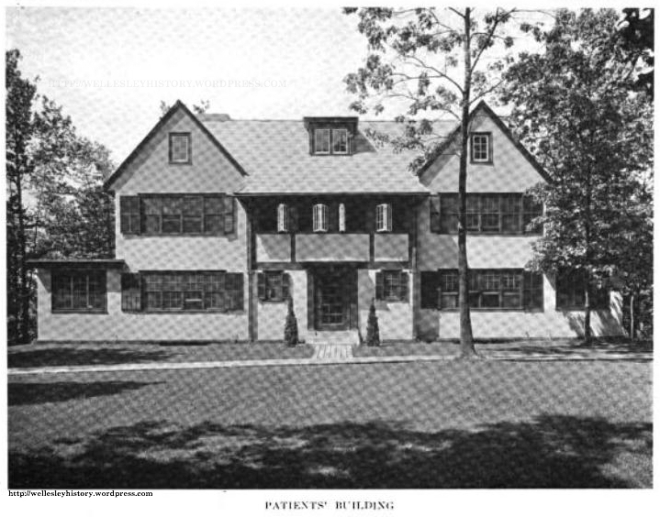

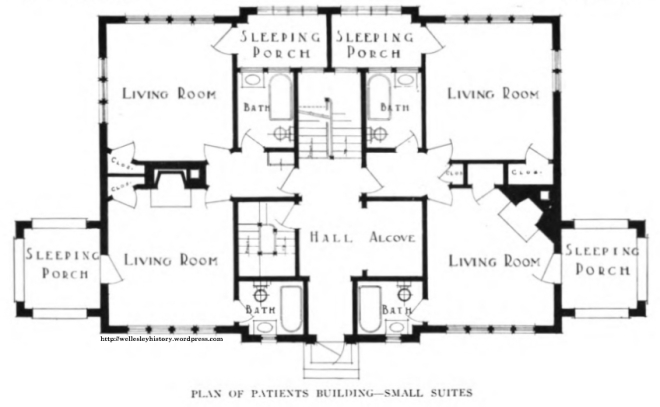

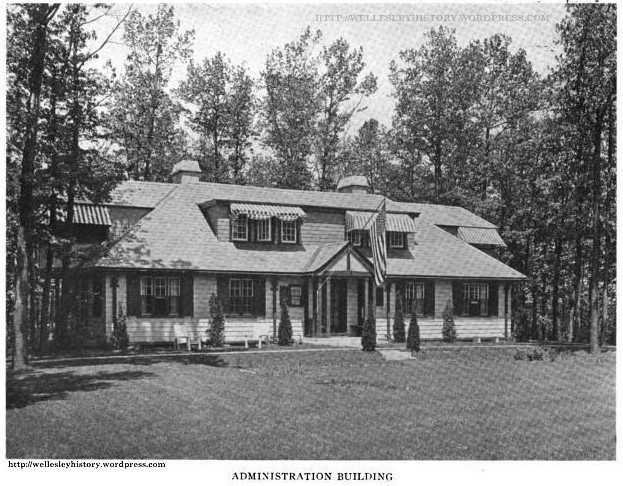

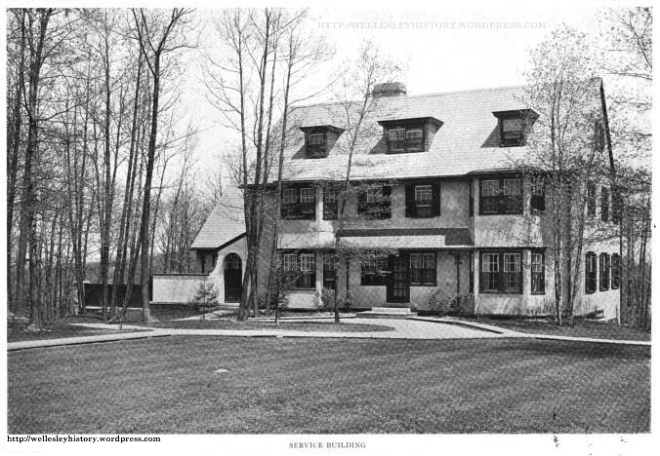

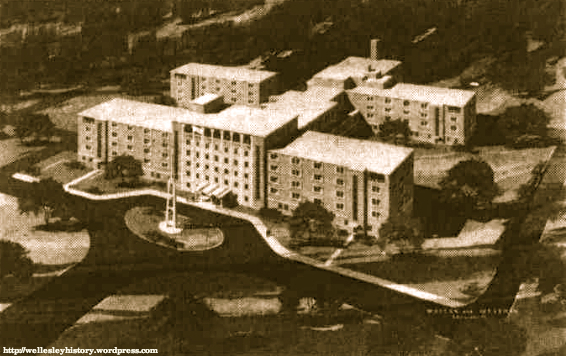

So, in 1966, the Church began construction on the new Mount St. Vincent Sister Formation Center. One could think of this facility as more or less a mini-college where up to 150 young women would study and train to become Sisters of Charity for the Boston and New York orders. In addition, there would be living quarters for a hundred current and retired sisters.

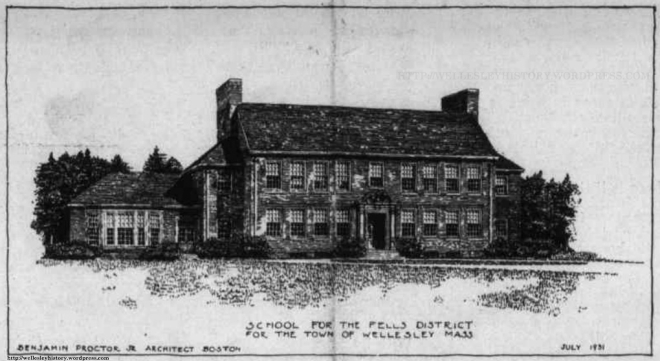

Sketch of Mount St. Vincent Sister Formation Center

Note that only front half of proposed building was constructed

(Posted with permission from the Wellesley Townsman)

At first, the new high school and Formation Center looked like they just might help the Catholic Church overcome its problems. Enrollment at the high school increased. And when the Formation Center opened in late 1967, there were 20 postulants (first year students) and 18 novices (second and third year students).

By 1971, however, the future looked less bright. Fundraising efforts to pay off the debts accrued during the construction of the Elizabeth Seton High School and the Formation Center had failed miserably. Furthermore, enrollment at the Academy was not high enough and the Formation Center was not bringing in as many teachers as the Church had hoped. Therefore, discussions to close the entire academy began.

Despite a frantic movement to save the school, it was announced in February 1971 that the academy would close after the 1971-72 school year. (By that point in time, the Formation Center had already been discontinued.)

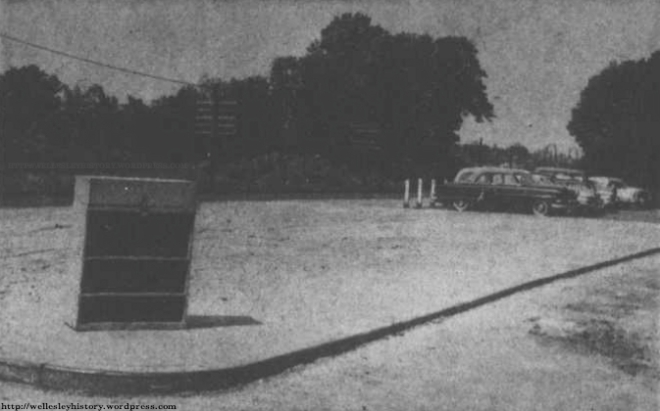

Town officials immediately began salivating at the prospect of acquiring a vast amount of land in a nearly built up town. Proposals percolated. They could build a new high school there. Maybe construct municipal offices. Perhaps leave a large area as open space. But a vote to purchase the property for $6 million failed (82-118) at a Special Town Meeting in June 1971.

In swooped Mass Bay Community College (which was then located on the Watertown-Waltham line). Two months later, a deal was made between the Sisters of Charity and Mass Bay to sell the main part of the campus to the community college provided that the Commonwealth could allocate the money. (It did.) The 84-acre property was sold for $5,390,500 in October 1973. Despite strong objections by the townspeople, Mass Bay opened in the fall of 1974.

Of course, the Town didn’t come away empty-handed. As a consolation prize, it was able to snag 42 acres of the former Academy farm (for only $1.1 million!) in 1980 for Centennial Park, the Town’s present to itself for the approaching 100th anniversary of its separation from Needham.

Today, the only physical reminders that the Academy of the Assumption was a significant part of Wellesley for nearly eighty years are a few campus buildings and structures as well as the Elizabeth Seton Residence.

Looking back on the last few decades of the Academy’s existence, was there anything the Sisters of Charity could have done differently to prevent the outcome that occurred? I’m not really sure.

On one hand, there are plenty of Catholic secondary schools still open in Massachusetts. Why not the Academy of the Assumption as well?

The facts, on the other hand, tell a different story. Between 1965 and 2014, the number of religious sisters nationwide has dropped by 72%, the number of priests by 35%, and the number of Catholic secondary schools by 22%. We’ve even seen the declining influence of the Catholic Church elsewhere in Wellesley, with the closure of St. James the Great in 2004.

I therefore suspect that the only way the Academy of the Assumption could have survived was if the Church had not acted so foolishly with its own money in constructing the Formation Center. Yes, the Academy would have had to rely on the Catholic laity to teach. But don’t you think that’s a much better scenario than what actually happened?

Note: All color photographs were taken by Joshua Dorin in July 2014.

Sources:

- Federal Census Reports of 1860, 1870, 1900

- Boston Daily Globe: 31 August 1875; 19 June 1892; 12 September 1893; 29 October 1967

- Life of Mrs. Eliza A. Seton, Foundress and First Superior of the Sisters or Daughters of Charity in the United States of America by Charles I. White (1880)

- A Directory of the Charitable and Beneficent Organizations of Boston by The Associated Charities (1891)

- The Sacred Heart Review: 15 September 1894; 7 August 1897; 27 August 1898

- One Hundred Years of Progress; A Graphic, Historical and Pictorial Account of the Catholic Church of New England; Archdiocese of Boston by James S. Sullivan (1895)

- Atlas of the Town of Wellesley, Massachusetts by Geo. W. Stadley & Co. (1897)

- The Catholic Directory, Almanac and Clergy List by M.H. Wiltzlus Company (1901)

- Wellesley Townsman: 29 May 1908; 28 November 1919; 16 June 1922; 14 July 1922; 4 May 1923; 22 June 1923; 12 June 1925; 18 January 1929; 23 March 1933; 1 June 1934; 29 November 1935; 3 June 1938; 24 May 1940; 18 November 1943; 18 September 1947; 30 September 1948; 21 September 1950; 24 May 1951; 29 November 1951; 14 February 1952; 22 May 1952; 19 March 1953; 23 September 1954; 12 May 1955; 23 June 1955; 24 May 1956; 20 September 1956; 8 November 1956; 25 May 1961; 16 November 1961; 23 May 1963; 31 October 1963; 12 December 1963; 17 September 1964; 2 September 1965; 19 May 1966; 23 June 1966; 26 October 1967; 14 January 1971; 28 January 1971; 25 February 1971; 24 June 1971; 12 August 1971; 26 August 1971; 8 June 1972; 11 October 1973; 5 September 1974; 15 May 1980

- The Book of Boston by Edwin Monroe Bacon (1916)

- The Reading Eagle: 17 January 1929

- 1931 Booklet for the Semi-Centennial of the Town of Wellesley

- Guide to the Religious Life: Archdiocese of Boston by Albert R. Mann (1945)

- The Sisters of Charity of New York, 1809-1959 by Marie de Lourdes Walsh (1960)

- Charity Alive: Sisters of Charity of Saint Vincent de Paul, Halifax, 1950-1980 by Mary Olga McKenna (1998)

- Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate — Frequently Requested Church Statistics — accessed in August 2014

- Norfolk County Registry of Deeds

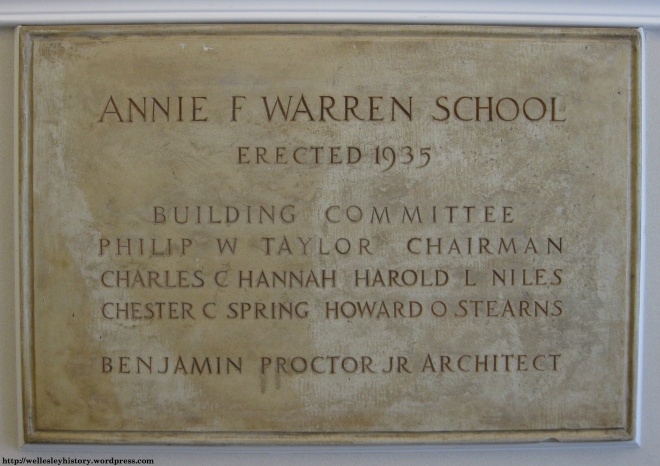

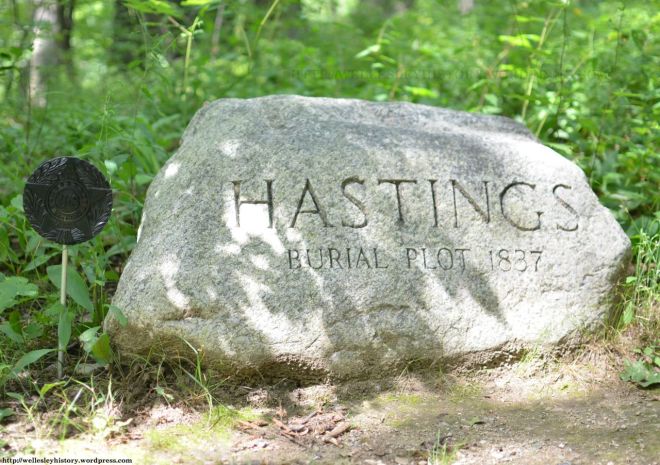

Bonus Photo: Anyone know the origins of this cornerstone? I suspect it came from the main building of St. Joseph’s Academy, which was razed between 1969 and 1971, but I’m not 100% sure.